To provide observations and information on the emerging fields of landscape scale conservation, heritage preservation, and sustainable community development.

Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the latest nature, culture and community news.

We won’t spam you or share your information. Newsletters are sent approximately 10 times a year. Unsubscribe at any time.

Cultural Heritage, Environmental Impact Assessment, and People

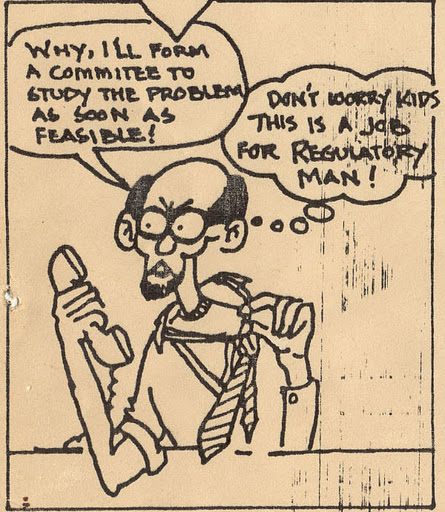

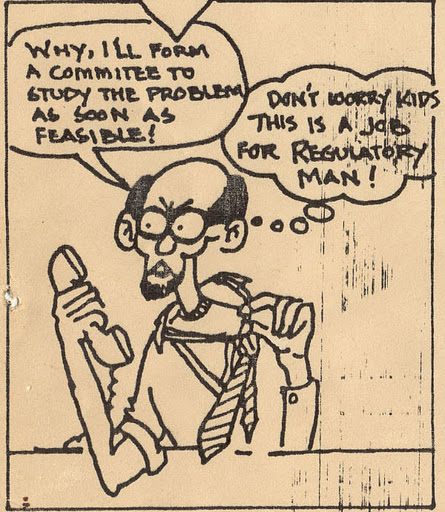

Government development projects, really any large infrastructure projects, have the potential to damage the environment, which includes its cultural heritage aspect. While most nations have put in place a process to assess such impacts, as applied to cultural resources the process seems formulaic, does not address impacts to the broader cultural landscape, and ignores or discounts what the communities value as their heritage and what is important for their living traditions.

The U.S. Biosphere Reserve Program: Can the challenges of the past contribute to the resiliency of the future?

It is easy to acknowledge our current state in UNESCO’s international Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program, but neglect to see how we got to this point. As one of the pioneers in large landscape conservation, biosphere reserves paved the path for many future landscape-scale efforts over the past several decades. Yet, most people in the United States are unfamiliar with the term, biosphere reserve, or assume the program has dissolved because of its long period of inactivity. Some people are trying to change this perception.

Invisible Landscapes: Why Historic Site Interpretation is Needed for Today’s Narrative

With the face of historic preservation changing from house museums with a specific perspective on society, it is important that we address those changes by countering it through the narrative of the other. Diversity in the field of historic preservation is something that we are just beginning to deal with, and by understanding the role of diverse people and communities in our past for what it was, we can encourage people to recognize themselves in today’s continued narrative. Having visited both Monticello and Mount Vernon quite recently, there was a distinct difference in the atmosphere between the slave memorial and Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon, and at Mulberry Row at Monticello. Read More.

Anthropogenic Landscapes: The Idea of PLACES

The following article theorizes that by arranging the occurrence of plants and animals into anthropogenic landscapes, ancestral Native Americans had developed new types of economic systems. Through managing nut groves, fruit orchards, and berry patches, utility and medicinal gardens for examples, close to their home-base residences, Native Americans were able to successfully and sustainably manipulate their environments, ensuring predictable yield, while decreasing effort and distance traveled to desired resources

Keweenaw National Historical Park: Just where is the Park?

Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula is an 800,000-acre land mass that extends out from Lake Superior’s southern shore. For over 7000 years, people have come to the peninsula to extract pure copper trapped in its ancient volcanic rock formations. The Keweenaw National Historical Park has developed creative ways to tell this story.

Cultural Heritage, Environmental Impact Assessment, and People

Government development projects, really any large infrastructure projects, have the potential to damage the environment, which includes its cultural heritage aspect. While most nations have put in place a process to assess such impacts, as applied to cultural resources the process seems formulaic, does not address impacts to the broader cultural landscape, and ignores or discounts what the communities value as their heritage and what is important for their living traditions.

The U.S. Biosphere Reserve Program: Can the challenges of the past contribute to the resiliency of the future?

It is easy to acknowledge our current state in UNESCO’s international Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program, but neglect to see how we got to this point. As one of the pioneers in large landscape conservation, biosphere reserves paved the path for many future landscape-scale efforts over the past several decades. Yet, most people in the United States are unfamiliar with the term, biosphere reserve, or assume the program has dissolved because of its long period of inactivity. Some people are trying to change this perception.

Invisible Landscapes: Why Historic Site Interpretation is Needed for Today’s Narrative

With the face of historic preservation changing from house museums with a specific perspective on society, it is important that we address those changes by countering it through the narrative of the other. Diversity in the field of historic preservation is something that we are just beginning to deal with, and by understanding the role of diverse people and communities in our past for what it was, we can encourage people to recognize themselves in today’s continued narrative. Having visited both Monticello and Mount Vernon quite recently, there was a distinct difference in the atmosphere between the slave memorial and Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon, and at Mulberry Row at Monticello. Read More.

Anthropogenic Landscapes: The Idea of PLACES

The following article theorizes that by arranging the occurrence of plants and animals into anthropogenic landscapes, ancestral Native Americans had developed new types of economic systems. Through managing nut groves, fruit orchards, and berry patches, utility and medicinal gardens for examples, close to their home-base residences, Native Americans were able to successfully and sustainably manipulate their environments, ensuring predictable yield, while decreasing effort and distance traveled to desired resources

Keweenaw National Historical Park: Just where is the Park?

Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula is an 800,000-acre land mass that extends out from Lake Superior’s southern shore. For over 7000 years, people have come to the peninsula to extract pure copper trapped in its ancient volcanic rock formations. The Keweenaw National Historical Park has developed creative ways to tell this story.