To provide observations and information on the emerging fields of landscape scale conservation, heritage preservation, and sustainable community development.

Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the latest nature, culture and community news.

We won’t spam you or share your information. Newsletters are sent approximately 10 times a year. Unsubscribe at any time.

Nantucket Island: Preservation Sans Connection

The built environment reflects the cultural, environmental, social, and historical identity of a community. What happens when another value, that of economic value, becomes the key consideration? Maanvi Chawala, a 2015 US ICOMOS international intern, examines this challenging topic in the context of Nantucket Island. Read the full article here.

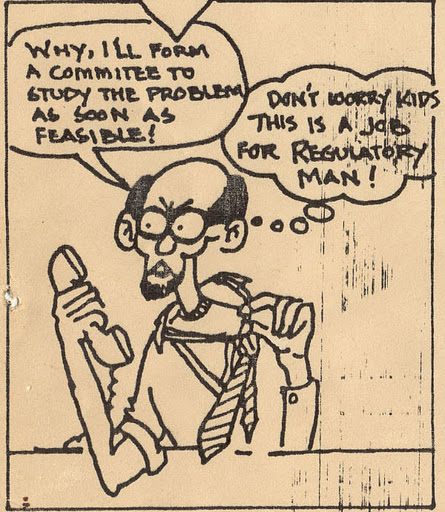

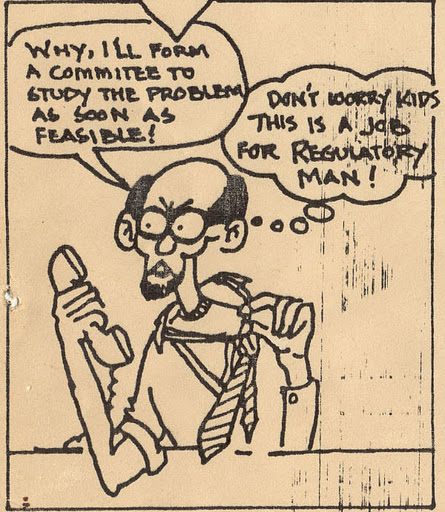

The 2016 Federal Budget: How did Large Landscapes Fare?

After months of uncertainty, weeks of negotiations and two short-term extensions to keep the government open, Congress passed and the President signed the 2009 page omnibus spending Bill, titled the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016. How did federal initiatives that support landscape scale work and fund our natural and cultural conservation program fare?

Jeju Island Korea Hosts International Experts on Cultural Landscapes

Jeju Island Korea offers a remarkable landscape of scenic beauty, rich heritage and future opportunities. It was the setting for the November 2015 Annual Meeting of the ICOMOS-IFLA International Scientific Committee on Cultural Landscapes (ISCCL). A meeting at which the conversation centered around the aesthetics of landscapes, connecting the practice of nature and cultural conservation, and an initiative to advance the understanding and conservation of world rural landscapes .

National Heritage Areas Deliver Place-Based Education

The thirtieth anniversary of the first National Heritage Area (NHA) and the upcoming centennial of the National Park Service (NPS), inspired research into the relatively untapped topic of the mutual benefits to both NHAs and the NPS. Recent research has explored how NHAs deliver place-based educational programming in partnership with nearby national park units.

Cultural Heritage, Environmental Impact Assessment, and People

Government development projects, really any large infrastructure projects, have the potential to damage the environment, which includes its cultural heritage aspect. While most nations have put in place a process to assess such impacts, as applied to cultural resources the process seems formulaic, does not address impacts to the broader cultural landscape, and ignores or discounts what the communities value as their heritage and what is important for their living traditions.

Nantucket Island: Preservation Sans Connection

The built environment reflects the cultural, environmental, social, and historical identity of a community. What happens when another value, that of economic value, becomes the key consideration? Maanvi Chawala, a 2015 US ICOMOS international intern, examines this challenging topic in the context of Nantucket Island. Read the full article here.

The 2016 Federal Budget: How did Large Landscapes Fare?

After months of uncertainty, weeks of negotiations and two short-term extensions to keep the government open, Congress passed and the President signed the 2009 page omnibus spending Bill, titled the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016. How did federal initiatives that support landscape scale work and fund our natural and cultural conservation program fare?

Jeju Island Korea Hosts International Experts on Cultural Landscapes

Jeju Island Korea offers a remarkable landscape of scenic beauty, rich heritage and future opportunities. It was the setting for the November 2015 Annual Meeting of the ICOMOS-IFLA International Scientific Committee on Cultural Landscapes (ISCCL). A meeting at which the conversation centered around the aesthetics of landscapes, connecting the practice of nature and cultural conservation, and an initiative to advance the understanding and conservation of world rural landscapes .

National Heritage Areas Deliver Place-Based Education

The thirtieth anniversary of the first National Heritage Area (NHA) and the upcoming centennial of the National Park Service (NPS), inspired research into the relatively untapped topic of the mutual benefits to both NHAs and the NPS. Recent research has explored how NHAs deliver place-based educational programming in partnership with nearby national park units.

Cultural Heritage, Environmental Impact Assessment, and People

Government development projects, really any large infrastructure projects, have the potential to damage the environment, which includes its cultural heritage aspect. While most nations have put in place a process to assess such impacts, as applied to cultural resources the process seems formulaic, does not address impacts to the broader cultural landscape, and ignores or discounts what the communities value as their heritage and what is important for their living traditions.