On a recent visit to the Presidio in San Francisco, a statement in the welcoming exhibit caught my attention. It announced that – as of February 2013 – the Presidio had became self-sustaining and went on to say that for every $1 of government money the site has generated $4 of private money. With all the news about the financial difficulties of supporting of parks and protected areas and the push from some quarters to require that these resources become self-supporting, I wanted to know more. A quick search found a recent article in the San Francisco Chronicle that reinforced the good news. Over the last 15 years, the Presidio Trust has developed a host of private-public partnerships, worked with Lucas Films and the Disney Family Museum, rehabilitated hundreds of historic properties, and leased 1,200 housing units constructed by the Army. Craig Middleton, Executive Director of the Presidio Trust, estimates that more than $1.2 billion in capital investment has gone into the Presidio. This was been important because under the terms of the federal law that created trust, it had just 15 years – until 2013 – to become self sufficient or the property could be sold off.

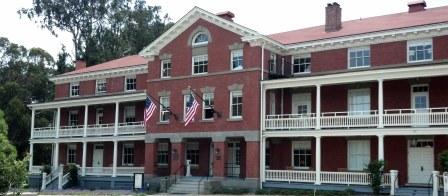

For over 200 years, the Presidio had been a strategic as well as outstandingly scenic location. Settled first by American Indians and then serving as a military post for the armies of Spain, Mexico and the United States. Today the site consists of 1,400 acres with over 800 buildings of which over 400 are historic structures. According to Lisa Benton Short in Presidio: From Army Post to National Park, the army played an early conservation role in developing the property. Beginning in the 1880’s, they planted over 80,000 trees and created scenic vistas, hiking trails and golf courses. The opening of the Golden Gate Bridge in 1937 and the designation of the road around the base as part of the 49-mile Scenic Drive in 1938 to promote the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition helped cement the public value of the place.

When the Presidio, along with over 500 military installations, was slated to be closed as part of the Defense Base Realignment and Closure Act of 1988, the public saw the potential for the property to offer open space conservation, recreation and spiritual renewal. There was strong support to incorporate it into the boundaries of the adjacent Golden Gate Recreation Area (GGRA). However, the price tag to operate the Presidio was a high barrier to its designation as a part of the national park system. In the early 90’s the Seventh Army was spending close to $70 million dollars to run the site. The National Park Service (NPS) estimated that it would take at least $24 million for them to manage the property, which although a reduction from the army’s costs, was still greater than the budget for Yosemite National Park. And there were high expectations, William Penn Mott, former NPS director, called for the agency to come up with a plan that was up to the stature of this world-class site.

The original 1994 NPS Management Plan for the Presidio did set a high bar. It recognized that this would be “a park like no other” and envisioned the Presidio managed by an innovative partnership to become “a global center dedicated to addressing the worlds most critical environmental, social and cultural challenges.” However, the plan needed the approval of the 104th congress whose members were staggered by the price tag at a time when deficit reduction was a congressional watchword. After much horse-trading, the bill for the park was signed in 1996. It did establishe an innovative public/private partnership to be known as the Presidio Trust and endowed it with wide latitude to borrow money from treasury ($50 million), guarantee loans, and demolish buildings that could not be re-used. The bill also added a provision that was not in the NPS plan. It required that the Presidio become self-sustaining in fifteen years or else its component parts would be sold on the open market.

At the time concerns were raised about this compromise, environmental advocates criticized the plans for the Presidio as being more of a “business park” than National Park. Scholars raised concern about the approach; see The Presidio Trust and our National Parks: Not a Model to be Trusted by Joanna Wald in the Golden Gate University Law Review. Today these debates about how much private development should occur at the Presidio are still ongoing, but taken, as a whole, the site is a spectacular peace dividend to the bay area and the nation.

Privatization of parks and other heritage resources or the more nuanced concept of public private partnership is an idea that goes in and out of favor. However, the need to craft partnerships, attract capitol, gain philanthropic support, and otherwise “merge economic reality with park stewardship” will probably be with us for a long time. State parks across the country have been pressured into new management approaches and big urban park systems are experimenting with new business models. But although the Presidio’s mission statement asserts that “The Presidio is a model of contemporary park making, ‘’ I suspect its model for self -sustainability is not likely to be replicated. Few organizations start with thousands of square feet of real estate in one of the US prime markets and are capitalized at a quarter of a billion dollars in public funds. And wait there is more; the Presidio also has the GGNR unit as a strong partner with a mission to assist them in interpretation, visitor services, and resource conservation.

Congratulations to the Presidio Trust and to everyone who has made it such a success. While we may not be able to duplicate the approach, what lessons can we learn from this experience to help all parks be better cared for in the future?