To provide observations and information on the emerging fields of landscape scale conservation, heritage preservation, and sustainable community development.

Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the latest nature, culture and community news.

We won’t spam you or share your information. Newsletters are sent approximately 10 times a year. Unsubscribe at any time.

Threats to the Conservation of U.S. Marine Landscapes

Overshadowed by the controversy over shrinking the size of national monuments that protect large swaths of the United States’ western landscapes, is a parallel effort to change the protected status of the nation’s marine resources. While all eyes have been focused on Department of the Interior, the Department of Commerce has been preparing its own report on the future of marine national monuments and national marine sanctuaries. The report is not yet public, but could impact a broad area of the nation’s off shore real estate.

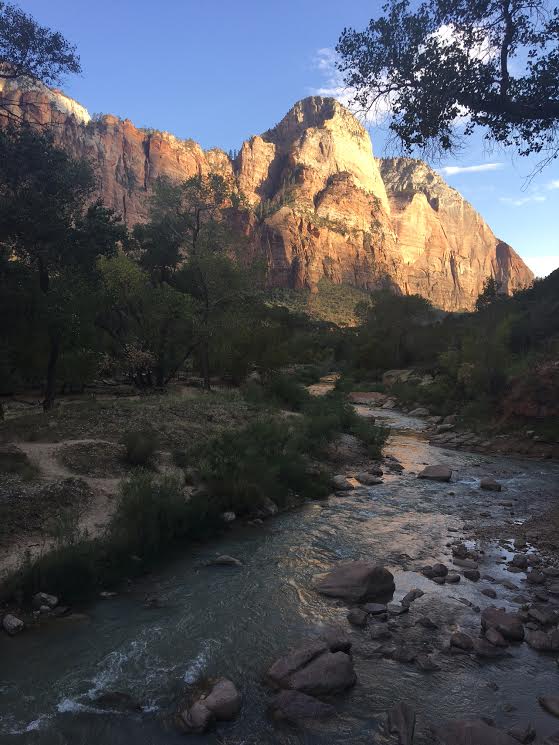

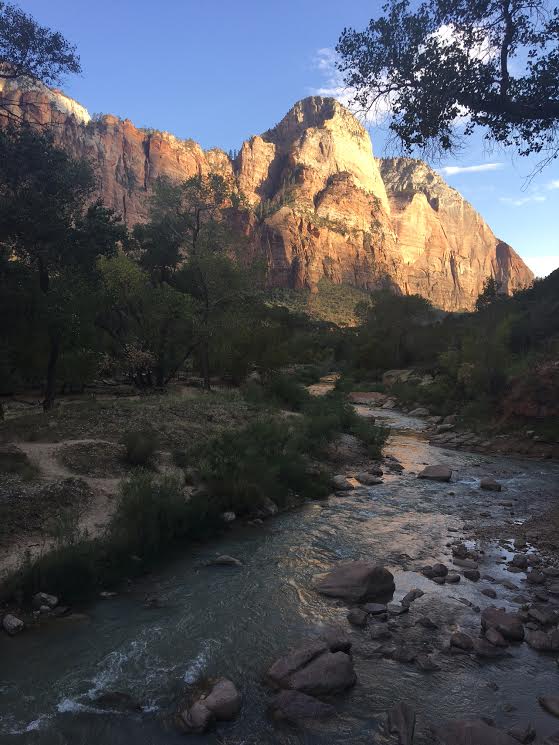

Edward Abbey: Seer in the Desert

Re-reading Edward Abbey’s 1968 classic Desert Solitaire, brought some new revelations beyond his lyric descriptions of the desert landscape and sketches of its memorable characters. The book offers some predictions and recommendations for the future of western rivers, National Parks and wilderness. So what were three of his most compelling observations?

The Future of the Bureau of Land Management’s Master Leasing Plans

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) with 247 million acres of public land in its portfolio and a multiple use mission that includes leasing authority for grazing, mining, oil and gas drilling as well as recreational activities has a challenging job. And nowhere is the work of BLM more difficult than in making leasing decisions adjacent to our National Parks. To help reduce conflicts between BLM practices and the need to protect park resources, the agency had adopted a landscape scale approach to reviewing proposed leasing known as Master Leasing Plans. But today this strategy may be at risk.

Worlds End Celebrates 50th Anniversary

2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the acquisition of the World’s End property in Hingham, Massachusetts, by the nonprofit Trustees of Reservations. World’s End is one of more than 100 properties managed by the Trustees, an organization that dates to the late 19th century. Read more.

Filling Mines with Fish: Rebranding the Mesabi Range as a Recreational Landscape

Post-mining landscapes often lie. What we see on the landscape today does not necessarily reflect the history in which that landscape was shaped. In this piece, guest observer John Baeten explores the complex story of Minnesota’s Mesabi Iron Range, tracing the effects of heritage tourism and environmental reclamation on a region long known as a center of extractive industry

Threats to the Conservation of U.S. Marine Landscapes

Overshadowed by the controversy over shrinking the size of national monuments that protect large swaths of the United States’ western landscapes, is a parallel effort to change the protected status of the nation’s marine resources. While all eyes have been focused on Department of the Interior, the Department of Commerce has been preparing its own report on the future of marine national monuments and national marine sanctuaries. The report is not yet public, but could impact a broad area of the nation’s off shore real estate.

Edward Abbey: Seer in the Desert

Re-reading Edward Abbey’s 1968 classic Desert Solitaire, brought some new revelations beyond his lyric descriptions of the desert landscape and sketches of its memorable characters. The book offers some predictions and recommendations for the future of western rivers, National Parks and wilderness. So what were three of his most compelling observations?

The Future of the Bureau of Land Management’s Master Leasing Plans

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) with 247 million acres of public land in its portfolio and a multiple use mission that includes leasing authority for grazing, mining, oil and gas drilling as well as recreational activities has a challenging job. And nowhere is the work of BLM more difficult than in making leasing decisions adjacent to our National Parks. To help reduce conflicts between BLM practices and the need to protect park resources, the agency had adopted a landscape scale approach to reviewing proposed leasing known as Master Leasing Plans. But today this strategy may be at risk.

Worlds End Celebrates 50th Anniversary

2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the acquisition of the World’s End property in Hingham, Massachusetts, by the nonprofit Trustees of Reservations. World’s End is one of more than 100 properties managed by the Trustees, an organization that dates to the late 19th century. Read more.

Filling Mines with Fish: Rebranding the Mesabi Range as a Recreational Landscape

Post-mining landscapes often lie. What we see on the landscape today does not necessarily reflect the history in which that landscape was shaped. In this piece, guest observer John Baeten explores the complex story of Minnesota’s Mesabi Iron Range, tracing the effects of heritage tourism and environmental reclamation on a region long known as a center of extractive industry