It should be no surprise to readers of the Living Landscape Observer that conserving large landscapes in the current political climate is challenging. While the inevitable negative impacts of the recent shutdown (December 22, 2018 – January 25, 2019) represent the most immediate threats to the management of public lands and federal programs that conserve our cultural and natural resources, the bigger issue is the underlying erosion of landscape scale work throughout our national government.

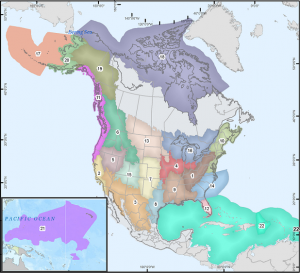

The 2015 American Academy of Science report “An Evaluation of the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives”, identified the need for a landscape approach to resource conservation. The report noted that geographic scale and the complex web of management responsibility for natural and cultural resources demand a collaborative approach to conservation and that this is especially true in times of scarce resources. Only through this approach can the nation address such systemic challenges as conserving wildlife habitat, combating invasive species, protecting cultural landscapes, and planning for climate change. The Landscape Conservation Cooperatives (LCCs) were designed to provide a framework for federal agencies to meet these challenges. And of course, they were one of the first programs to be dismantled.

Courtesey NOAA

Another set of actions that has had an outsize impact on large landscape conservation is the ongoing reduction in public land protections. In 2017, for example, the Trump administration launched a review of 21 national monuments. The most publicized outcome of this process has (thus far) been the shrinking of Bears Ears National Monument. Within the borders of this monument alone, the potential losses are tremendous – decreased protection for an estimated 100,000 archaeological sites as well sites with significance for paleontology and geology. Even more important, the landscapes of the monument have tremendous ongoing cultural importance for many Indigenous peoples in the region. Shrinking Bears Ears is a lost opportunity to manage part of the country’s heritage on a landscape scale and to do so in partnership with the Native nations that have lived upon and cared for these lands for generations untold. Read more here.

Bears Ears National Monument as well as another Utah national monument, Grand Staircase Escalante, were not the only places that have suffered reduced protection. Protection for marine reserves have also been reduced. Overshadowed by the controversy over shrinking the size of national monuments that protect large swaths of the United States’ western landscapes, is a parallel effort to change the protected status of the nation’s marine resources. While all eyes have been focused on Department of the Interior, the Department of Commerce has prepared its own report to review the size and protection offered to six national marine sanctuary expansions and five marine national monuments. Read More here.

Courtesy of the US Fish and Wildlife Service

Less reported on – but also a real calamity – is the dismantling of the multi state effort to save the Greater Sage Grouse. Spurred to action by strong interest in preserving the bird and its habitat and concern about a possible endangered species listing many agencies and organizations came together to protect the species over a large landscape. These efforts to conserve greater sage-grouse habitat were not limited to state and federal agencies. Industry and private landowners also developed means of conserving greater sage-grouse. The Sage Grouse Initiative has worked with more than 1,129 ranches to conserve more than 6,000 square miles of sage-grouse habitat in 11 western states. Although hailed as a conservation success, in 2018 the Department of the Interior decided to revise this broadly backed and science-based approach. The proposed changes could have significant and far-reaching effects on sage-grouse in America—specifically by weakening protections on the landscapes the species calls home. Read More here.

Across the board the budgets for large landscape programs have been slashed whether it is the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives or the National Heritage Areas. And that does not even begin to touch on what is happening to climate change research. However, as we start 2019, we do have a few bright spots. Private organizations are stepping up. The new Network for Landscape Conservation has dedicated a lot of energy to the effort to bring conservation to scale. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy has launched a comprehensive landscape scale initiative

States are also continuing to support landscape scale conservation. North American fish and wildlife agencies have recommitted themselves to coordinated conservation strategies on a national and international scale. See Association of Fish and Wildlife Organization’s Strategic Plan Goals 3. States like Pennsylvania are expanding support for innovative Conservation Landscape efforts. Virginia has adopted a new Conservation Vision to guide development on a landscape scale.

All these efforts are praiseworthy, but we still need federal agencies at the table. A couple of points to consider:

- Because of the pattern of land ownership in the United States, large landscape work west of the Mississippi must engage Federal partners. If those essential partners are not engaged in these efforts, the work becomes immensely more problematic. For example, the reduced size of both Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments eliminated protected status for more than 2 million acres of land in Utah alone.

- Federal partners bring more than just land ownership. Until recently they brought a powerful voice for a landscape ethic, partnership programs like the Landscape Conservation Collaboratives and landscape programs in the Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management and even the Department of Defense have played a critical role in making the landscape approach work.

- In addition to other actions the administration has delayed re-appointments to friends groups and Advisory boards. They might as well post a big sign “Not Open for Partnership Business.” Well not completely, the federal government is open for other business such as the business of extractive industries as demonstrated by, increase in drilling permits alone. And these interests have no reason to embrace landscape conservation. Under the current administration there is hardly even a nod to the landscape benefits to the recreational industry or to gateways communities. Issues were on the table during the last republican administration of George W Bush.

Of course, all this makes total sense, if as the National Academy report states, landscape scale work is powered by the need to address issues like unregulated development, energy extraction, and climate change. Seen through this lens, the idea of landscape scale conservation is in clear opposition to the current administration’s agenda.

So, what can we do?

Many groups are tackling pieces of the puzzle by pushing back with activism on specific issues and if needed law suits– see the work of the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks. Other are working harder to be successful in their own bailiwick such as the Network for Landscape Conservation. But there is also a need to call out this dismantling of critical Federal programs and partnerships as what it is – a systemic challenge to landscape scale thinking. Perhaps we need a more unified platform, a bigger vessel in which to track the risks to this important work. We need to merge the agendas of nature and culture conservation not just around protected lands, but in advocating approaches that engages all partners and incorporate our lived in landscapes toward achieving conservation goals at scale.