The word landscape jumps out at you on many of the interpretative signs at Mesa Verde National Park and the real thing is before you at every overlook. The park established in 1906, ten years before the creation of the National Park Service, was later designated as the first World Heritage cultural site in the United States (1978). The original motive for creating the park came out of a growing interest in the archaeology of the Southwest that also lead to the creation of national monuments such as Chaco Canyon, Bandelier, Hovenweep and Aztec Ruins. What made Mesa Verde standout to the early settlers and explorers were the extensive ‘cliff houses and ancient ruins’. In 1892 the writer Frederick Chapin visited one of the larger sites and described it as “occupying a great oval space under a grand cliff wonderful to behold, appearing like an immense ruined castle with dismantled towers.”

In part it was this cross-cultural comparison of the structures to European building types that focused attention on Mesa Verde as something special in North America – a place that needed to be preserved. This was not to say the that the artifacts associated with the site were not seen as important. In fact, the designation was made more urgent by the continued threat of pothunting and vandalism of the sites in the cliffs and on the mesa tops.

For years Mesa Verde National Park was described as a place shrouded in mystery. The people who lived there were portrayed as having suddenly abandoned the cliff dwelling and just disappeared. The builders were labeled the Anasazi a term derived from the Navajo word meaning ‘ancient ones’ or alternatively ‘ancient enemies’, which added to the confusion. Now we know that these people did not disappear, but migrated south to become the ancestors of the modern-day pueblo and Hopi people. Today park interpretation refers to the cliff dwellers as Ancestral Puebloans who like so many people around the globe migrated to other places for other opportunities.

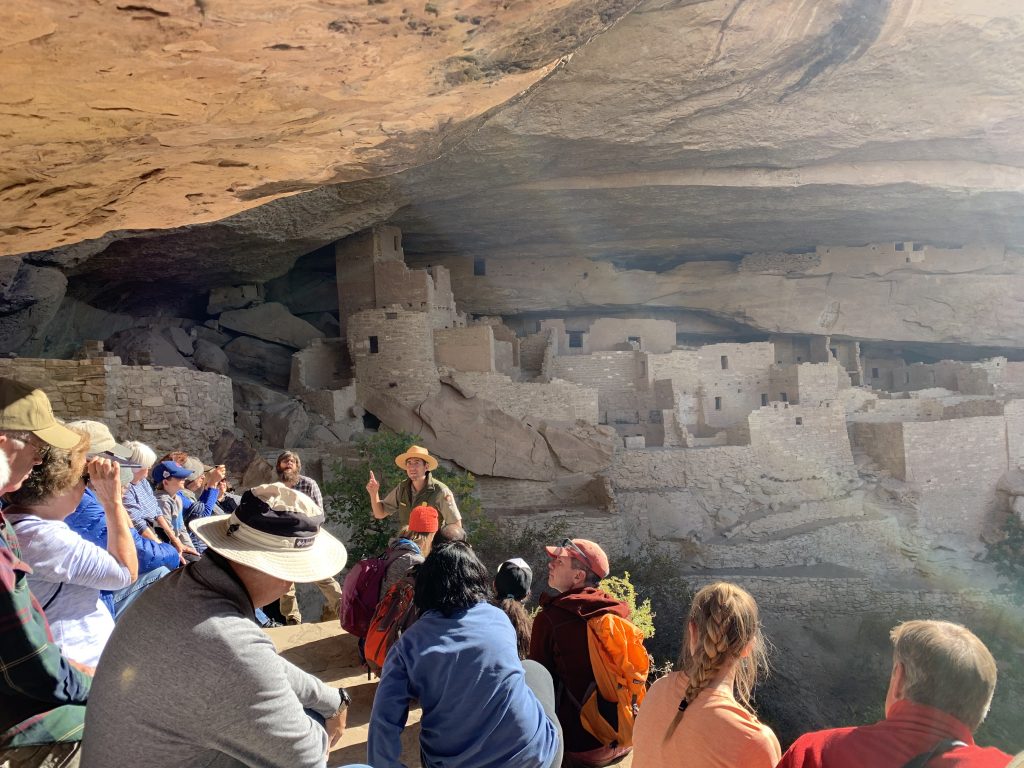

Just as importantly, current research places the people of Mesa Verde in a much larger regional context. Settlements that date from between 350 BC and AD 1300, the span of settlement on Mesa Verde, are found throughout southwestern Colorado and in the Four Corners region. Current research also links the people of Mesa Verde to one of the centers of Puebloan culture Chaco Cultural National Historical Park another World Heritage site (1987). As our ranger said on a recent tour of Cliff Palace, by the 1200s the region had a larger population than live here today. He told us that if we could have looked out from the tops of the mesas at night, we would see the fires from towns and villages that spread to the horizon. This image helps visualize the peopling of the region at a landscape scale.

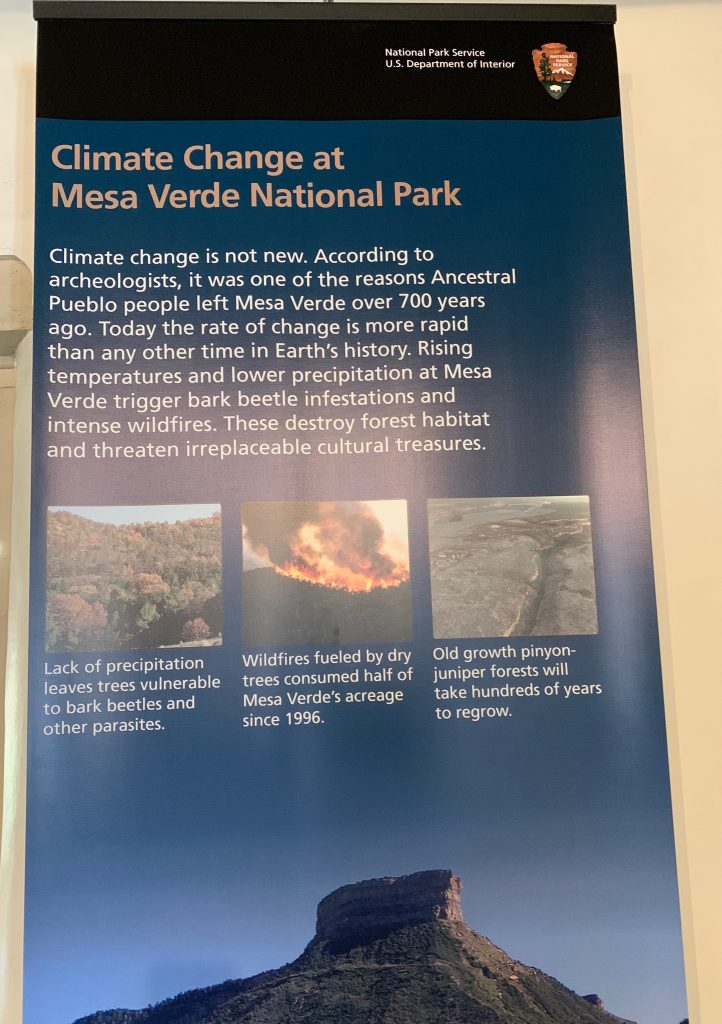

The newer interpretation gives visitors a better understanding of the past population of Mesa Verde, but does not answer the question of why did they leave the region after 1300s? Possibly for some the same threats that hover over the Mesa Verde today – changes in the environment and changes in climate. The park has not shied away from this topic. A recent study has shown that today’s hot and dry conditions in Mesa Verde have exceeded climates fluxes in the past. A park resource manager noted that nearly 70% of the landscape in the 52,485-acre park has been altered in just the last few decades for reasons that tie directly back to climate change. Namely, drought-driven fires.h

This has had a severe impact on the mesa top landscape fires have been able to take hold that have burned off acres and acres of the pinon-juniper forests. While periodic droughts were common to the region in the past, the current level is unprecedented. A 2016 UNESCO report on World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate hspecifically identified the park as facing serious risks rising temperatures and declining rainfall. A combination could cause increased wildfires that might irreversibly damage the park.

How is the park telling these newer stories? First, by recognizing the ancestral Puebloan roots of the people of Mesa Verde in park waysides and in ranger talks and programs, and also by offering forthright statements on climate change. A prominent banner in the Chapin Museum states that while climate change has always been with us “Today the rate of change is greater than in any other time in the earth’s history.”

Mesa Verde National Park has relatively lower visitation (563,000 in 2018) compared to some other parks on the Colorado Plateau with over 1.5 million visors a year. However, it is no backwater when it comes to sharing the latest findings in history and science.

Congratulations to all!