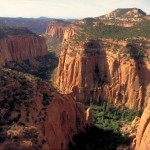

Courtesy: Bureau of Land Management

National Monuments were once an obscure protected area designation. Today they are a big story in major news outlets. Reporters are struggling with names likes Bears Ears, Grand Staircase – Escalante, and Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. What put these places in the headlines was the new administration’s signature on an April 26, 2017 Executive Order authorizing a review all National Monuments designated since January 1, 1996 and specifically those over 100,000 acres.

The press coverage usually gets the origin story right. The Antiquities Act passed in 1906 during the administration of Theodore Roosevelt. It authorized the president by proclamation to set aside land owned or controlled by the federal government for conservation purposes. This power has been used by 16 presidents of both parties for over a hundred years to create 170 national monuments. However, there are some ongoing misconceptions. The biggest one is that the designation locks up private lands.

The legislation is clear that monuments are to be created out of the public estate or lands that have been donated for public purposes. However, general readers might conclude from the rhetoric in the press that this is a Federal land grab. To start with the President called it a land grab when he signed the E.O. And a Utah local government official is quoted in the New York Times as saying., “You just don’t take something from somebody,” equating the designation of Bears Ears as a national monument to grand theft. In Maine, where one family has donated over 87,000 acres to the Department of Interior to create the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, opponents claimed the land would be better returned to timber production. But, as noted by Lucas St. Clair, a spokesperson for the family, in an interview with the Guardian: “This was private land that my family owned and wanted to donate to create a national park… they (opponents) fail to realize the land was sold to us by people from the forest products industry because it was no longer valuable to them as a landscape to log and cut trees…the argument that this is taking this land out of potential fiber production is absurd.”

Courtesy: National Park Service

Another source of confusion is what National Monument status means. The New York Times opined that, in terms of protection, national monuments are generally considered one step below national parks. Some of this confusion may be caused by the different agencies tasked with managing the individual monuments. For example, Grand Staircase – Escalante is managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Papahānaumokuākea is administered jointly by three co-trustees – the Department of Commerce, the Department of the Interior and the State of Hawai’i. But just to set the record straight those National Monuments managed by the National Park Service are part of the National Park system and are not second class citizens.

The size of monuments also appears to be a concern. And this is in part because the Antiquities Act states that a monument “be confined to the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.” Secretary Zinke raised this issue at his confirmation hearing and it is reflected in the recent order to review the larger sized monuments. But, as a recent well researched post in the National Trust Forum notes, some monuments are “pretty monumental” take the Grand Canyon. And we can add the Grand Tetons and multiple parks in Alaska to the list.

Courtesy: NOAA

There are also some big unknowns. Just what will happen if some of the national monuments are rescinded or boundaries adjusted. Drill rigs are pictured in many environmental alerts on the topic and that is certainly a possibility. And opponents talk about the limits monument designation may impose on economic activity such as logging, and oil and mineral extraction. However, the local people of San Juan County Utah are more likely objecting to the designation of Bears Ears because they want more control over their place on the earth. President Trump certainly played to this theme. In signing the April Executive Order to study the targeted monuments by saying “Today I am signing another E.O. to end another egregious abuse of Federal power and to give that power back to the states and to the people where it belongs”.

Department of Interior Secretary Zinke, who has the challenging task of implementing the study, has taken another path. Many of his public statements have been supportive of continued federal ownership of public land. See the Living Landscape Observer Listening to Zinke. So how will this all play out?

One discouraging sign is that despite his declarations about the importance of listening to residents and affected communities, Zinke issued a Department of Interior memo (May 5, 2017) sending a temporary stop work order to over 200 Department Advisory Committees. The stated goal is to review the charter and charge of each committee and as a spokeswoman for the department said “to restore trust in the Department’s decision making.” However, many of the committees, as has been pointed out by their members, were created to give local community input. Just one example, the 16-member, volunteer Acadia advisory commission was created by Congress in 1986 in response to community concerns about the park expanding its boundaries without adequate input. Membership is primarily 10 local governments adjacent to the park. Now government decisions are being made while they sit on the sidelines. Even more ironic, the agency’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument advisory committee will be suspended throughout the debate over the monument’s future.

With all of this is happening in the very short time frame of 120 days, it is hard to even set the record straight on what national monuments are or are not, before other changes may be proposed to this venerable conservation program.