In this issue we will consider the need to manage rural landscapes and their heritage values sustainably. In Australia sustainable management has usually referred to private lands and one of the driving forces in this management has been through Landcare for the last 30 years. This has also spawned other groups practising organic, biodynamic and regenerative farming. At the national level, there is no sustainable agriculture policy despite two decades of a fragmented, stop-start approach. Australia’s only substantial sustainable agriculture policy mechanism seems to be grants available through the National Landcare Program which are around A$1 billion from 2017 to 2023. And even though these grants are substantial, past Australian Bureau of Statistics surveys found that farmers invest at least A$3 billion a year in natural resource management. Around 10% of Australia’s population lives in rural or remote areas. These comparatively small communities – largely farmers and Indigenous land managers – currently steward most of the country. The following case studies illustrate their work in terms of the application of World Rural landscape principles.

C 1. Consider bio-cultural rights within food and natural resource production. Implement planned management approaches that acknowledge the dynamic, living nature of landscapes and respect human and non-human species living within them.

Case Study: Spinifex Lands

The Anangu Pila Nguru (Spinifex People) are using a combination of traditional and contemporary land management practices to reduce threats and keep the people, culture and land healthy. The land area ranges from the Nullarbor Plain to the south, spinifex and sandhill country to the north and a variety of land forms incorporating salt lakes, rocky outcrops, hills, valleys and open plains with a wide range of desert marsupials, birds, plants and insects. A Healthy Country Plan developed by local rangers and the community provide direction and technical support. A standard Land Access and Mineral Exploration Agreement was the template developed to protect areas of cultural significance .

The Spinifex Land Management Program is based in Tjuntjuntjara, the second most remote community in Australia. The Healthy Country Plan covering 95,000 square kilometres has key projects including reducing the threats of buffel grass, camels, altered fire regimes, and introduced predators. They aim for total eradication of buffel grass from their lands within 10 years. Buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris) is widely recognised as the single greatest invasive species threat to biodiversity across the entire Australian arid zone as it is a “transformer species” that alters natural environments. It out-competes native plants, increases fire intensity, degrades native wildlife habitat and can outcompete bush tucker food plants for Indigenous people. Whereas traditional Aboriginal patch-burning encouraged regrowth of native grass species, the intense heat produced by burning buffel grass destroys native plants both above and below ground. Aboriginal women are reluctant to undertake traditional gathering practices because thick buffel grass decreases visibility of snakes (/). This community won the 2017 Western Australian Indigenous Landcare Award for following both traditional Pila Nguru Anangu (Spinifex people) land care practices and fresh responses to new environmental threats.

C. 3. Consider the connections between cultural, natural, economic, and social aspects across large and small landscapes, in the development of sustainable management strategies for rural landscapes as heritage resource.

Case Study: Reviving hedge laying, Tasmania

The original hedge fences planted by convicts in the 1820s-30s around farming land in the early colony fell into disrepair 60 or 70 years ago. Growing hedges as living fences was the latest agricultural innovation in England in the 1820s and came to Australia with the first settlers. They using local plants like the prickly mimosa which grows on some of the hills but it was not suitable for hedging so imported hawthorn [Cretagus spp.) which grew particularly well in Tasmania.

The Dumaresq family, sixth generation farmers, have employed James Boxhall, one of Australia’s few traditional hedge layers to trim them again, lay them over in the traditional way and bring them back into traditional working order over ten years. The satisfaction of preserving these ancient hedges and passing on a dying craft has kept people like Mr Boxhall on the job, cutting, pushing, bending and chainsawing the thorny and at times nasty plants back into the shape of the traditional fences. Twenty-first century hedge laying involves a mix of traditional and modern skills using the ancient cutting tool, the billhook, and the modern chainsaw, which allow the hedge layers to get through a restoration more quickly than their forebears. It is an expensive, long term, 10 year plan for the Dumaresqs.

Only 3,000 kilometres of historic hawthorn hedges remain. Encouraging people to have their hedges laid instead of pulling them out leads to restoration of a beautiful thick hedge adding value to a property. Some farmers see them as a hindrance to modern larger fields and conservationists see them as exotic plants harbouring feral fauna. Hedges are an important aesthetic component of the Tasmanian cultural landscape of farm lands and not protected by legislation so appealing to owners to look after them is necessary .

C. 6. Support the equitable governance of rural landscapes, including and encouraging the active engagement of local populations, stakeholders, and rural and urban inhabitants, in both the knowledge of, and responsibilities for, the management and monitoring of rural landscapes heritage.Because many rural landscapes are a mosaic of private, corporate, and government ownership, collaborative working relationships are necessary.

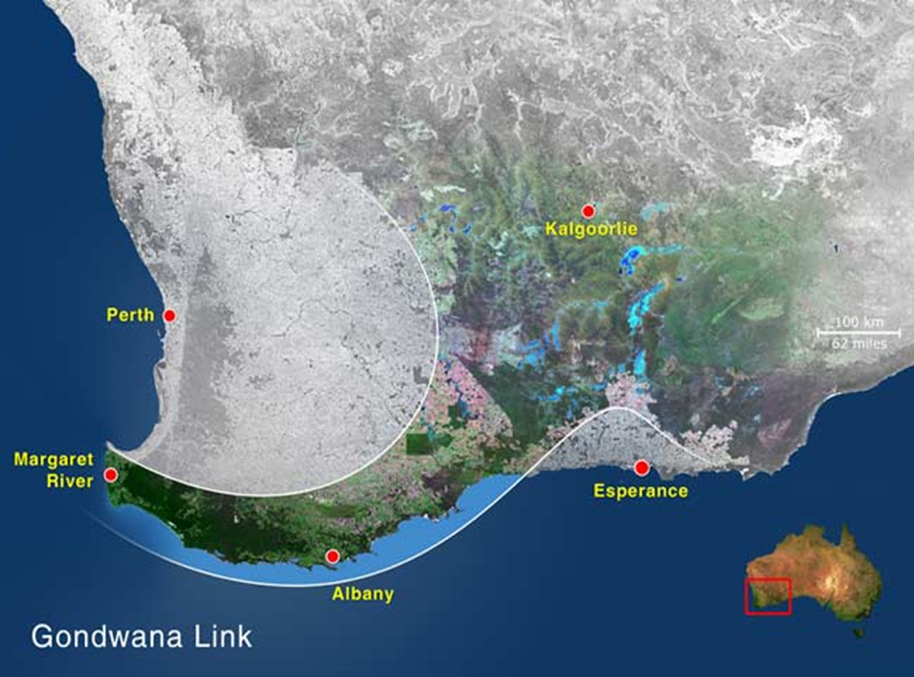

Case Study: Gondwana Link, WA

To achieve a band of healthy, reconnected bush across south-western Australia, one of the world’s 25 biodiversity hotspots, Gondwana Link aims to create 1,000 km of continuous habitat from the dry woodlands of the interior to the tall wet forests of the far south-west corner. Two-thirds of the vegetation had been cleared but within 900 kms patches of the original habitat is relatively intact, making the gaps of cleared land the key restoration focus. Now entering its 18 th year, Gondwana Link is an inspiring example of a cohesive effort by a broad spectrum of local, regional, national and international groups, private landholders and Indigenous communities. This is landscape repair at a mega-scale (). To restore habitat and heal country in the Gondwana Link, Greening Australia is working with Nowanup Rangers on a unique eco-cultural project. Under the shadow of the Stirling Ranges National Park mountains, tree planting is incorporating traditional designs of Noongar culture. This eco-cultural restoration approach recognises the age-old connection between the Indigenous community, plants and animals, and the landscape reconnecting habitat so wildlife can move between the region’s national parks across the wheatlands and sheep farms and help ensure the survival of endangered species such as the Carnaby’s Black Cockatoo.