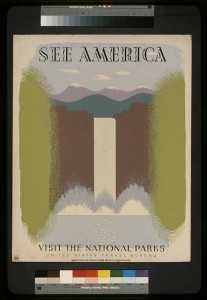

Earlier this month, the Creative Action Network and the National Parks Conservation Association launched an inventive crowd-sourced visual arts campaign called the “See America Project.” The initiative gets its name from a series of posters created by artists working for the Federal Art Project (FAP) during the 1930’s. One of several New Deal art programs, the FAP aimed to put unemployed artists back to work on a wide variety of tasks. Indeed, just in Washington State (which I researched for the Great Depression in Washington State Project), artists painted murals, did easel paintings, organized a successful art center in Spokane, created dioramas and demonstrated fabric arts. Across the country, artists also joined together to organize collectively in hopes of improving working conditions and wages and making the program permanent.

The FAP was one of several cultural ventures launched by the Roosevelt administration during the summer of 1935. Housed within the Works Progress Administration (WPA), these creative programs were collectively known as Federal One and also included the Federal Theatre Project, the Federal Writers Project, the Federal Music Project and the Historical Records Survey (originally part of the Writers Project). Together, they represented a key element of the “Second New Deal,” a period (1935-1938) when landmark programs like Social Security and the National Labor Relations Act were first implemented. For those wondering, funding for most post office murals did not come from the WPA; instead, officials at the Treasury Department selected which works would be installed. See a few of the WPA See America posters here.

The See America concept, however, goes back further than the New Deal era. According to research done by scholars Marguerite S. Shaffer and Cory Pillen, the original See America campaign was launched by the Salt Lake City Commercial Club in 1905 in the hopes of generating tourist revenue that was ostensibly being lost to Europe. Other tourism officials soon picked up on the campaign, making it a national trend. This is only of many examples of the connection between parks and commercial tourism prevalent in this period, perhaps best captured by the relationship between railroads and the development of the NPS.

These early materials and the later WPA posters tended to represent an idealized, tourist friendly idea of the American landscape. For example, imagery associated with Indigenous peoples was quite common, yet the reality of dispossession, so fundamental to the creation of public lands in the United States, utterly disappeared from view – an especially noteworthy omission as the early years of the 20th century marked the high point of land loss facilitated by the Dawes (General Allotment) Act.

I have had a great time looking at the new See America Project submissions and I applaud the wonderful creativity of the artists, who have the freedom to imagine and present sites however they wish. My hope for this 2014 series is that it can avoid the romanticizations and omissions of the past and instead embrace images of the landscape that capture and celebrate the ongoing interactions of diverse people and places throughout the United States. I would love to see images of people working, in addition to recreating, as well as of national historical parks that capture difficult, but important, moments in American history. And, since it is NHA@30, I would also love to see some heritage areas, which are rich in labor history and cultural traditions.

Sources:

Pillen, Cory. 2008. “See America: WPA Posters and the Mapping of a New Deal Democracy”. Journal of American Culture. 31, no. 1.

Shaffer, Marguerite S. See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880-1940. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001.