In March 2019, President Trump signed the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act (Dingell Act) into law. The bill, one of only a few major pieces of legislation to emerge successfully from the 116th Congress, had significant implications for the country’s public lands. Among the many notable provisions included in the act: 1.3 million acres of new wilderness, five new national monuments, and permanent re-authorization of the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

In addition, the bill also designated six new national heritage areas (NHA) – the first time in almost a decade that Congress added landscapes to the NHA system. Of particular importance, four of the six new NHAs were located in western states. This is noteworthy because the vast majority of NHAs are east of the Mississippi River in cities and regions with limited federal government land ownership.

The Pacific Coast, especially, has lacked in representation with no NHAs located in California, Washington State, or Oregon – until this year. The Dingell Act established one new NHA in California, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta National Heritage Area, and two in Washington State, the Mountains to Sound Greenway National Heritage Area and the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area.

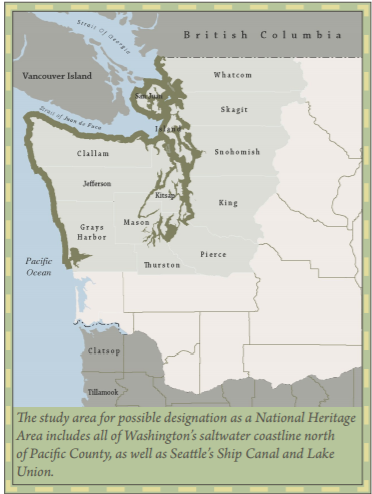

The Maritime Washington NHA is an especially remarkable addition to the NHA program owing to its explicit focus on marine landscapes, including historic vessels. The NHA boundaries are the saltwater coastlines of 14 counties or roughly 3,000 miles of shoreline .25 mile from the mean high water mark. These boundaries encompass parts of major cities like Seattle and Tacoma, dozens of smaller towns, National Historic Landmarks and National Register districts, and lands under local, state, and federal jurisdiction. Tribal lands could also be included if a tribe chooses to participate. The lands and waters of the entire region have been and remain homelands to Coast Salish peoples.

The drive to create a maritime heritage area in Washington State has been underway for well over a decade. Efforts initially coalesced around a remarkable collection of historic vessels and related-maritime history in the Seattle area and expanded from there. In the mid-2000’s, advocates, with important support from the Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (DAHP), began a four year public engagement process that culminated in publication of a feasibility study in 2010.

The in-depth outreach, which has continued since the study’s completion, included a year speaking to city councils, county commissions, local economic development agencies, the public and port commissions about the value of a maritime heritage area. In addition to the DAHP, key early partners included the Washington Trust (Trust) for Historic Preservation, the National Park Service (NPS) and the Pacific Northwest Maritime Heritage Council. The Trust is the designated management entity for the NHA. The final bill had the strong support of the Governor, both Senators and the Congressional delegation that represented the coastline districts.

The feasibility study emphasized the connectivity of Washington State’s coastal areas, recognizing that since time immemorial salt water has tied the region together. It also highlighted the importance of Washington’s coastline to regional, national, and international history. The study highlighted five goals for the proposed NHA, public awareness, including at a national level, economic development via heritage tourism, capacity building for local organizations, support for working waterfronts, and environmental restoration.

These aims mirror those found in many NHAs, with the exception of one – support for working waterfronts. Washington ports and the connected marine businesses contribute billions to the economy of the state. These are truly working landscapes. They are also contested landscapes. Organized labor, multi-national corporations, environmental activists, commercial and recreational anglers, government agencies, and more all have a voice and stake in these places. Indigenous peoples also have treaty rights to these lands and waters and play an integral role in their management.

The scale and scope of Washington’s working waterfronts represent a new type of challenge for the NHA program. The incipient Maritime Washington NHA will have to balance the competing needs, interests, and perspectives of dozens, if not hundreds, of stakeholders. This is daunting – yet the purpose of the NHA model is to address just this type of challenge.

The core function of any NHA is collaboration. NHAs are platforms for relationship building and partnerships. Management planning is the forum for developing common goals and aspirations for the next ten to fifteen years. It is a critical period for any NHA. This is why federal support is so important – but, unfortunately, the six new NHAs are facing a difficult funding environment. Designated in March 2019, they will not receive any monies this year. The potential for a continuing resolution means that appropriations might not arrive until 2021 – a full two years into the legislatively mandated three-year planning cycle. This will affect all the new NHAs as they undertake the robust public engagement and research processes necessary for management planning.

The Dingell Act also signaled a change in the legislative language governing NHAs. In the past, NHAs often had robust individual bills that contained numerous specific provisions relative to each heritage area. In this bill, the authorizing language for each NHA was brief. Instead, a longer section contained common generic elements that pertained to each NHA. Overtime it will be interesting to see how this new approach affects NHAs – if at all.

No other NHA has been as focused on the water and water-based resources as the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area. Its designation will raise the visibility of maritime resources and history in the state, while also offering new opportunities for collaboration and partnership building among diverse stakeholders in the public, nonprofit, and private sectors. The history and contemporary perspectives of Native peoples will be also central to the effort. Protected areas managed by all levels of government will have a chance to exchange knowledge and expertise, as will workers in marine industries.

Thanks to Dr. Allyson Brooks, State Historic Preservation Officer/Executive Director Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation and Chris Moore, Executive Director, Washington Trust for Historic Preservation, for their perspectives on the new National Heritage Area.