To provide observations and information on the emerging fields of landscape scale conservation, heritage preservation, and sustainable community development.

Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the latest nature, culture and community news.

We won’t spam you or share your information. Newsletters are sent approximately 10 times a year. Unsubscribe at any time.

Protecting America’s Long Trails

October, 2018, marks the 50th anniversary of two remarkable federal laws: the National Trails System and Wild and Scenic Rivers Acts. Both laws set up ways that the federal government can assist in protecting and operating “long, skinny corridors” for recreation and heritage resource preservation. The key to the success of these corridors across the landscape and along our waterways has always been partnerships. Federal agencies working with private citizens and dedicated volunteers, have created irreplaceable links to our cultural and natural heritage.

Virtues of Good Government

In this piece, originally published in the May 2017 issue of the George Wright Forum (vol 34, no 1), guest observer Rolf Diamant explores the

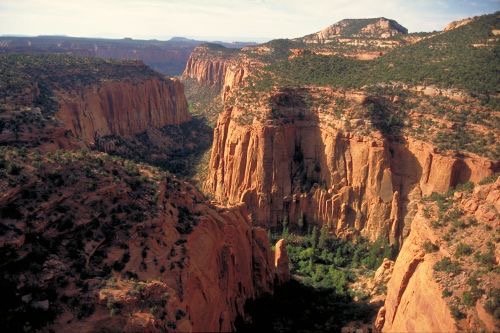

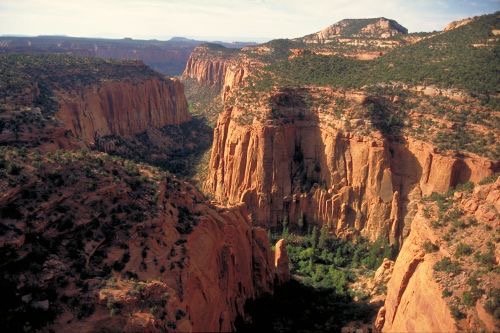

What is in a name? The National Monument Version

National Monuments were once an obscure protected area designation. Today they are the big story in major news outlets. Reporters are struggling with names likes Bears Ears, Grand Staircase – Escalante, and Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. What put these places in the headlines was the new administration’s signature on an Executive Order authorizing a review all National Monuments designated since January 1, 1996 and specifically those over 100,000 acres. The rush is on to learn more about national monuments.

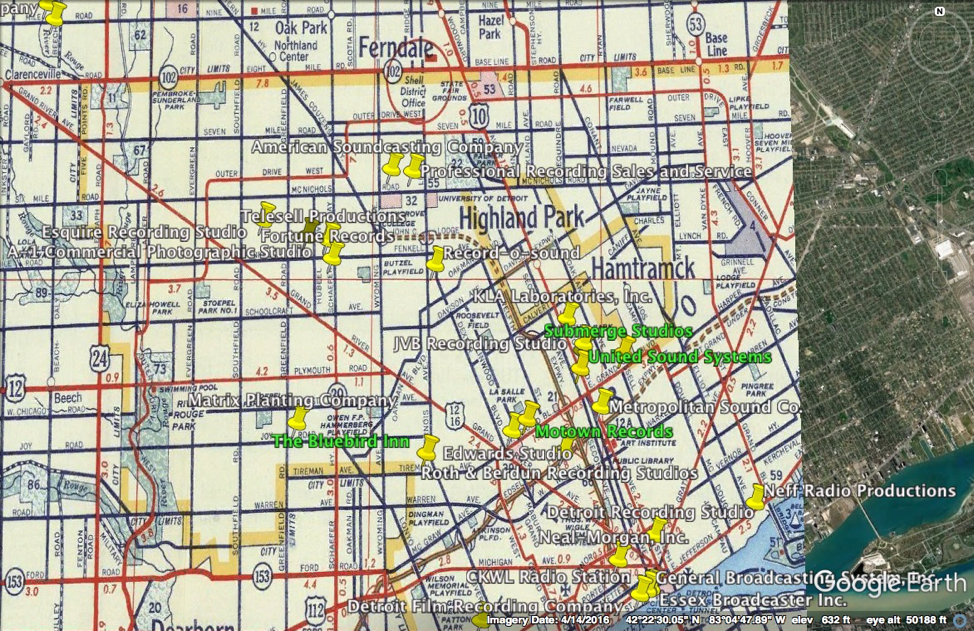

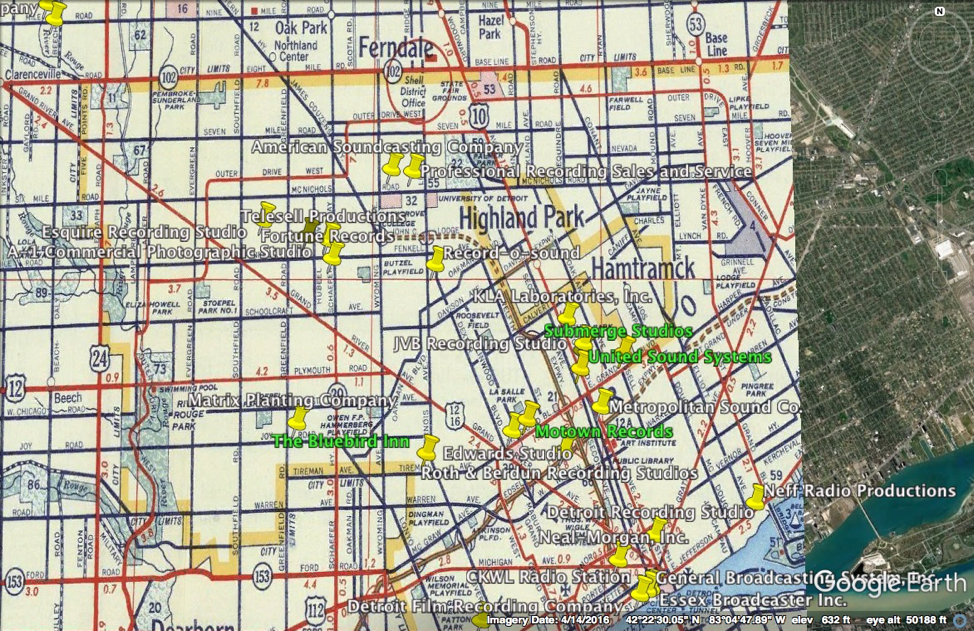

Looking for Detroit’s Urban Landscape: My Experience on the George Wright’s 2016 Park Break

Detroit is a place indelibly marked by the highest highs and the lowest lows of American history. Its crumbling buildings and forgotten factories are the tangible evidence of economic booms and busts, the rise and decline of American manufacturing, and the after-effects of WWII, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, racism and classism, as well as decades of local mismanagement and corruption. It also has a rich urban cultural heritage that is still visible on the landscape, if you look closely enough. Read about one student’s experience seeking this heritage as part of the George Wright Society’s Park Break program, which in 2016 focused on implemtning the National Park Services Urban Agenda.

Examining Federal Land Acquisition Practices After World War II

In the decades after World War II, the Federal government significantly altered its approach to land acquisition for parks, forests and other protected areas. Before this

Protecting America’s Long Trails

October, 2018, marks the 50th anniversary of two remarkable federal laws: the National Trails System and Wild and Scenic Rivers Acts. Both laws set up ways that the federal government can assist in protecting and operating “long, skinny corridors” for recreation and heritage resource preservation. The key to the success of these corridors across the landscape and along our waterways has always been partnerships. Federal agencies working with private citizens and dedicated volunteers, have created irreplaceable links to our cultural and natural heritage.

Virtues of Good Government

In this piece, originally published in the May 2017 issue of the George Wright Forum (vol 34, no 1), guest observer Rolf Diamant explores the

What is in a name? The National Monument Version

National Monuments were once an obscure protected area designation. Today they are the big story in major news outlets. Reporters are struggling with names likes Bears Ears, Grand Staircase – Escalante, and Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. What put these places in the headlines was the new administration’s signature on an Executive Order authorizing a review all National Monuments designated since January 1, 1996 and specifically those over 100,000 acres. The rush is on to learn more about national monuments.

Looking for Detroit’s Urban Landscape: My Experience on the George Wright’s 2016 Park Break

Detroit is a place indelibly marked by the highest highs and the lowest lows of American history. Its crumbling buildings and forgotten factories are the tangible evidence of economic booms and busts, the rise and decline of American manufacturing, and the after-effects of WWII, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, racism and classism, as well as decades of local mismanagement and corruption. It also has a rich urban cultural heritage that is still visible on the landscape, if you look closely enough. Read about one student’s experience seeking this heritage as part of the George Wright Society’s Park Break program, which in 2016 focused on implemtning the National Park Services Urban Agenda.

Examining Federal Land Acquisition Practices After World War II

In the decades after World War II, the Federal government significantly altered its approach to land acquisition for parks, forests and other protected areas. Before this