To provide observations and information on the emerging fields of landscape scale conservation, heritage preservation, and sustainable community development.

Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the latest nature, culture and community news.

We won’t spam you or share your information. Newsletters are sent approximately 10 times a year. Unsubscribe at any time.

Cultural Landscape Foundation Features Duncan Hilchey Interview

Government Shutdown: US National Park Service in the Spotlight

New Monuments, Old Debates

On July 10, 2015, President Obama used his authority under the Antiquities Act to designate three new National Monuments – Berryessa Snow Mountain in California, Waco Mammoth in Texas, and Basin and Range in Nevada. With these new designations, the President will have used the Antiquities Act to establish or expand 19 national monuments. First used by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, the Antiquities Act remains one of the most important – and most controversial – tools by which the Executive Branch can take immediate action on pressing conservation and preservation priorities.

Economic Change and Park Policy

Political economy has long shaped park policy in the United States. Beginning in the late 19th century when the booming railroad business drove the designation of new National Parks to more recent shifts towards privately-funded public spaces, protected areas have always reflected the dominant economic ethos of an era. What can we learn about post World War II park-making by looking at the changing role of the state and the increasing mobility of capital during that time period?

George Wright Conference Highlights Large, Living Landscapes

Writers and contributors from the Living Landscape Observer will be participating and presenting in a variety of sessions at the 2015 George Wright Conference that begins today (March 30) in Oakland, CA and runs through the end of the week.

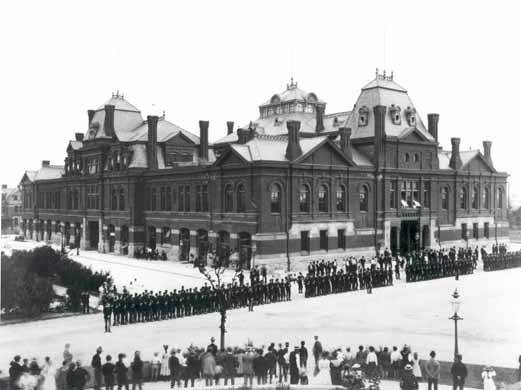

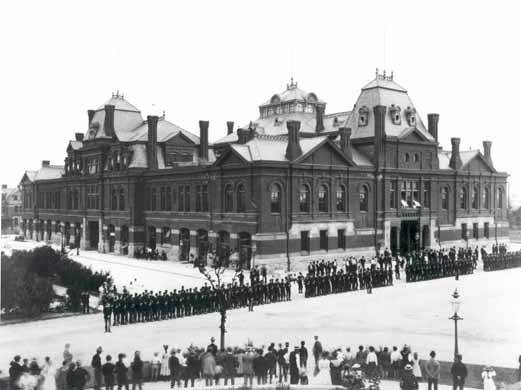

Labor History Makes Headway in NPS

Roughly a week ago, President Obama designated Pullman (IL) a National Monument under the Antiquities Act. The community is home to rich histories, which shaped both the labor and civil rights movements. Yet, it remains one of only a handful of NPS units that examine industrial work and collective action on the part of labor to any significant degree.

Sustainability – is it really what we want?

What does it mean for new types of parks and protected areas, like heritage areas, to be financially “sustainable”? Is that the best approach to the conservation of complex, lived-in landscapes or does it lead to unrealistic goals, especially in the realms of fundraising and yearly operating budgets.

New Monuments, Old Debates

On July 10, 2015, President Obama used his authority under the Antiquities Act to designate three new National Monuments – Berryessa Snow Mountain in California, Waco Mammoth in Texas, and Basin and Range in Nevada. With these new designations, the President will have used the Antiquities Act to establish or expand 19 national monuments. First used by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, the Antiquities Act remains one of the most important – and most controversial – tools by which the Executive Branch can take immediate action on pressing conservation and preservation priorities.

Economic Change and Park Policy

Political economy has long shaped park policy in the United States. Beginning in the late 19th century when the booming railroad business drove the designation of new National Parks to more recent shifts towards privately-funded public spaces, protected areas have always reflected the dominant economic ethos of an era. What can we learn about post World War II park-making by looking at the changing role of the state and the increasing mobility of capital during that time period?

George Wright Conference Highlights Large, Living Landscapes

Writers and contributors from the Living Landscape Observer will be participating and presenting in a variety of sessions at the 2015 George Wright Conference that begins today (March 30) in Oakland, CA and runs through the end of the week.

Labor History Makes Headway in NPS

Roughly a week ago, President Obama designated Pullman (IL) a National Monument under the Antiquities Act. The community is home to rich histories, which shaped both the labor and civil rights movements. Yet, it remains one of only a handful of NPS units that examine industrial work and collective action on the part of labor to any significant degree.

Sustainability – is it really what we want?

What does it mean for new types of parks and protected areas, like heritage areas, to be financially “sustainable”? Is that the best approach to the conservation of complex, lived-in landscapes or does it lead to unrealistic goals, especially in the realms of fundraising and yearly operating budgets.