Over the past two decades, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has dramatically expanded its involvement in planning and conservation on a landscape scale. It has done this in partnership with other federal agencies, state government, Indigenous nations, and non-profit organizations.

During the past two years, however, much of this work has been refocused, especially in the realms of planning, partnerships, and science. The future is now uncertain with competing interests making predictions difficult. The administration tends to defer to state and local government, over federal management, but still aims to prioritize the needs of industry, even when these goals conflict with local prerogative.

To complicate matters further, in mid-July, the Department of the Interior announced that BLM headquarters would be moving from Washington, D.C. to Grand Junction, Colorado. An official statement from DOI leadership touted the plan as a means to improve efficiency and decrease costs. The underlying motivations behind the decision, however, are potentially far more worrisome.

Only a small percentage of BLM employees currently work in the Washington office, about 400 out of a national staff of roughly 10,000. The main functions of these workers are planning, policy, budget, and legislative affairs. The proposed relocation would scatter the bureau’s Washington D.C. based employees nationwide, sending them to state offices as well as to the new, much smaller headquarters in Colorado. Critics argue that the plan is, at its base, an attempt to weaken oversight of public lands and shift authority from career staff to political appointees in the Interior Department – with the end goal of expediting energy and mineral development and commercial grazing.

What does all this mean for the agency’s large landscape initiatives?

In order to get insight into the future of this work and the potential implications of the BLM headquarters move, the Observer talked to Kit Muller. Recently retired from the BLM after a 38-year career with the bureau, Muller spent much of the past two decades working to better understand (and respond to) the impacts of landscape-scale changes on the American West, including climate change, wild land fire, invasive species, urban growth and industrial development. The following is a summary of our conversation, edited for clarity.

Many of our readers may be more familiar with other public lands agencies like the National Park Service or the U.S. Forest Service. Can you tell us a little bit about the BLM?

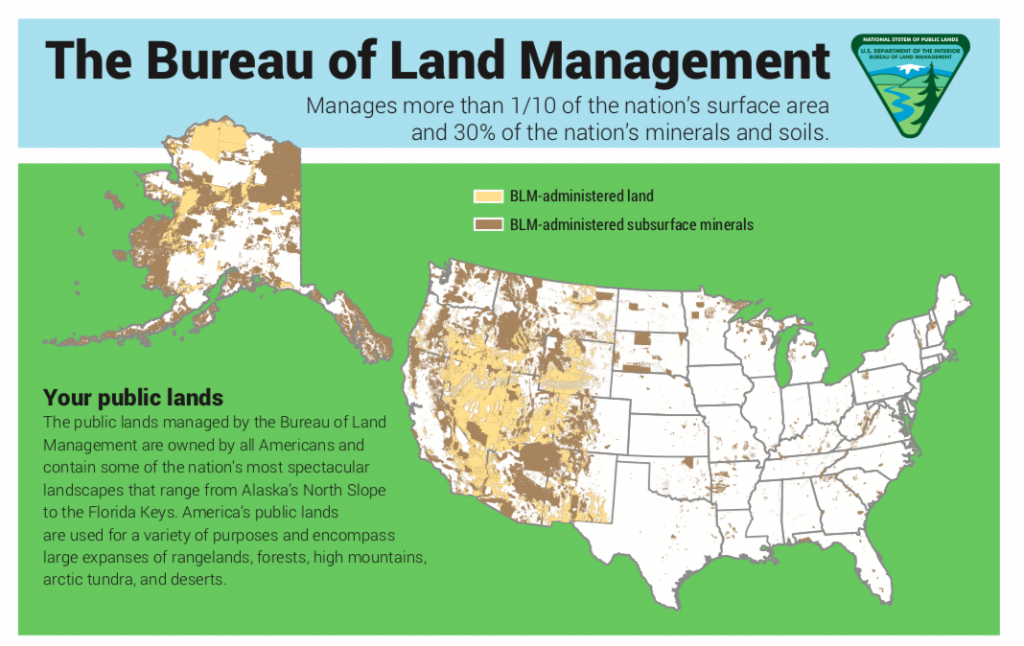

The BLM was created in 1946, following the merger of DOI’s General Land Office (GLO) and the U.S. Grazing Service. It manages about 10% of the U.S. land area, with most of that concentrated in 12 western states, including Alaska. Created in 1812, the GLO was the oldest land management agency in the U.S. For most of its history, it was dedicated to surveying the public domain and transferring it to private parties.

The BLM has a dual mission – multiple use and sustained yield, as mandated by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976. The multiple use aspect has long been dominant. With its roots in the GLO, the BLM has traditionally managed use rights, not resources. It was only with the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act, the Endangered Species Act, and other environmental and preservation laws that the bureau really began to consider the impacts that use rights could have on the environment.

Could you tell us more about the bureau’s large landscape work?

Since the second half of the George W. Bush administration, the bureau’s landscape work has been expanding. This picked up significantly during the Obama administration, but has now slowed considerably under current DOI leadership.

Four areas should be highlighted.

1) Planning

Before the 2000s, BLM rarely did planning on a landscape scale. The one exception was the Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP). Adopted in 1994 under the Clinton Administration, the NWFP covered BLM lands (along with lands managed by the USFS) in western Washington, Oregon, and northern California. Drafted in response to the listing of the northern spotted owl as an endangered species, the plan forced the bureau to think on a bigger scale and to work with a range of partners.

More recently, the bureau built on this work to collaborate on three additional landscape-scale planning efforts – the Greater Sage Grouse conservation plans, the plan for the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, and the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan in California.

In each of these cases, the bureau had to work with diverse partners from multiple levels of government, the private sector, and nonprofits. For example, the historic Sage Grouse plans (since altered under the current administration) involved the BLM, the USFWS, the U.S. Forest Service, state agencies in 11 states, and private landowners across a 173 million acre landscape.

2) Data Collection

At the same time that the bureau expanded its planning efforts, it also began to take data collection more seriously. Before 2004, data was primarily collected on a project-by-project basis – for an individual grazing allotment, for example, a mine site or well-pad – rarely systematically across a landscape. That changed owing to pressure and encouragement from the OMB as well as internal support. OMB said the BLM needed to be more systematic in its monitoring activities and offered funds to the bureau to get started. Partnering with ARS, NRCS, USFS, USGS, and EPA, over the last decade the BLM has established core indicators, standard data collection methods, and statistically based sampling frameworks for monitoring.

The results were pretty astounding. BLM now has standardized data on the aquatic and terrestrial condition of much of the public lands it manages This allows managers to make decisions based on standardized data from the field in addition to relying on their own expertise and experience. More training is still needed to apply this across-the-board and to discuss its importance to partners. BLM is also now collecting data about the disturbance “footprint” associated with the projects it authorizes.

3) Science

Initially recommended during the George W. Bush administration, a National Science Committee was established during the Obama Administration involving managers from many levels of the bureau. Its goal was to advance science in the agency and ensure that best practices were integrated into decision-making on a daily basis.

4) Partnerships

The idea of cooperative conservation gained significant traction in the bureau over the last two decades. In addition to the partnerships involved in the above mentioned planning efforts, the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives (LCC) are a prime great example of this. The 22 LCCs brought together federal,and state, governments, along with Indigenous nations, nonprofits, and universities to work together on a landscape scale. Addressing climate change was one primary aim of this initiative.

How was the current administration affected these efforts and what will be the impact of the proposed headquarters relocation?

Right now, we are in a period of commodity ascendency. This is not the first time this was occurred. There was a period of commodity ascendency under Interior Secretary James Watt in the early 1980s and then again when Vice President Dick Cheney played a dominant role in public lands management in the first term of the George W. Bush administration.

So far, the current administration has re-done the plans for the National Petroleum Reserve and for the Greater Sage Grouse. They have also been promoting oil and gas development to the detriment of conservation and other uses. The role of BLM career staff in headquarters has been diminished significantly. Career managers and program leads are not privy to many conversations and are sidelined in the decision-making process – one might say that the goal is to make the BLM headquarters irrelevant. So many of career staff members are in acting positions or on detail, expertise is being lost. Also, these individuals’ work on policy or budget development has been significantly curtailed. The Office of the Secretary is now routinely reviewing documents that were once approved without any Washington Office review. This is also a big change.

The landscape scale work is in jeopardy. Almost all the work of the LCC’s has been eliminated under the current administration. Plans are being re-done with significantly less emphasis on landscape considerations of condition and risk. The systematic collection and use of environmental data in decision-making are not management priorities. Without a well staffed and functioning Headquarters Office, it will be exceedingly difficult for the BLM to effectively participate in any regional or national interagency and intergovernmental conversations about natural resource management.