The story of organized labor in the United States is complex, powerful, inspiring, and infuriating. Millions of workers took collective action, often at risk of bodily harm or death, to better their lives and the lives of their peers. As a consequence of their bold efforts, regulations regarding work place safety, wages, hours, and overtime, now benefit large numbers of people employed in the U.S. – though millions still remain un-protected.

At the same time, however, the labor movement and its members generated policies and supported campaigns that espoused intense racism, xenophobia, sexism, colonialism, and homophobia. Most unions remained segregated by race well into the 20th century, for example, and hiring practices in many fields often benefited white, male workers to the detriment of women and people of color.

Across the country, hundreds of sites tell the story of organized labor in some fashion. However, there is no central means or mechanism to identify these locations. Roadside plaques and waysides are common, but because the entities behind these markers are so varied it is almost impossible to know the extent of signage and interpretation – or to understand how the stories might be connected on a larger scale. Highway transportation departments, state historic preservation offices, nonprofits, city government, local and international unions and more have all contributed. Cataloging all the locations and then mapping them might reveal new linkages within and across regions for example and motivate additional documentation efforts.

It would be fascinating to chart the age and locations of plaques and other signage. Where, for example, are markers related to the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) located? Also , what language is used? Are striking workers described as rioters or in more complimentary terms? Do signs acknowledge the boycott of Pullman Palace Cars on American railroads in 1894 or the grape boycott of the late nineteen sixties and seventies led by farm worker organizations, including the United Farm Workers (UFW)? Can signs be used to track the histories of the Knights of Labor or Pullman Porters?

Many signs came about as a result of grassroots organizing, and this part of the history also should be recognized. Perhaps new technologies can be harnessed (and likely have been already!) to expand the possibilities of these types of markers.

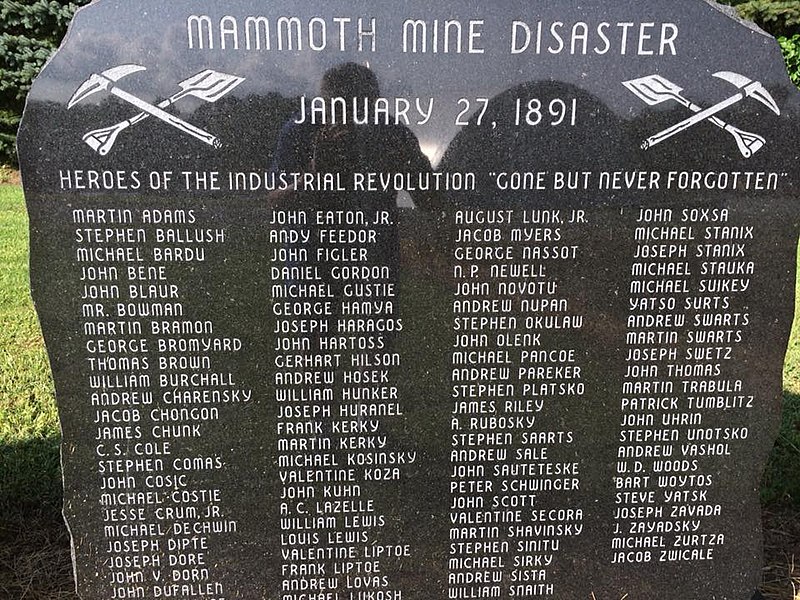

Memorial sites are another way that labor history is marked. These places acknowledge the danger of work as well as the danger of organizing at work. Some eulogize those who died on the job, others men and women killed by the military, law enforcement, and angry mobs during protests and confrontations. Creating a shared record of these somber locations would do much to aid our understanding of labor history and labor memory. How long after the fact are memorials created and who pays for their establishment and upkeep? Again, many are grassroots efforts owing to lack of interest or even active hostility of political leaders to acknowledge the violence that so often characterized corporate and government responses to worker organizing. Geographer Kenneth Foote has documented these types of cases in his 1997 book Shadowed Ground: America’s Landscapes of Violence and Tragedy.

Historic sites and structures that tell the story of the labor movement should also be better recognized and protected. These vary from structures in private ownership that have connections to workers’ struggles to museums and visitor centers. The American Labor Museum in New Jersey is one example. The museum is housed in the Botto House National Landmark, which is named for Italian immigrant and silk mill worker, Pietro Botto and his wife Maria. In the early 2000s, the National Park Service completed a draft Labor History Theme Study for the National Historic Landmarks Program. That document is now being updated and revised by Dr. Rachel Donaldson, who has written eloquently on connections between labor history and public history and the imperative to lift up workers’ voices and experiences when interpreting the history of work. (1)

Heritage Areas, at the state and national level, also deserve recognition. They include individual sites, but also significantly seek to interpret entire landscapes shaped by work. Heritage Areas highlight the connections between human and non-human nature and show connections across industries and ecosystems. In Pennsylvania’s Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor it is possible to trace the entire story of anthracite coal. Learning about extraction, processing, transportation, and distribution. Workers’ life stories become vivid as does the often times devastating impact of resource extraction.

Archives are important as well. Universities, including Wayne State, Washington, and Maryland, all hold impressive collections. These are also community hubs and meeting places and bring together different constituencies involved in documenting the story or work and collective action.

Ruins are another category that should be considered. All too often, the physical remains of labor have not been preserved. This can be true of housing, factories, meeting places, mines, mills, farm land, and more.

Finally, a listing of sites and stories that remain unmarked or unacknowledged is also vital. This could then inform future documentation initiatives.

Given the complexity and diversity of sites and stories involved, I believe it is time for action to create a new national network dedicated to the history of the labor movement. It could be created by Congress and administered by the National Park Service, as other networks have been – or perhaps it should be independent, with roots in labor and community organizations.

The creation of such a network would acknowledge the centrality of labor to telling diverse American and global stories. As union density has declined, so too has broad public understanding of their past and present role in shaping life at work and outside of work too (time for leisure is a key achievement of labor).

Such a network would also highlight the fabulous efforts already underway in many communities, especially the work of local, state, and regional labor history organizations, including the Illinois Labor History Society and the Pacific Northwest Labor History Association, among many others. Metropolitan labor councils have also done impressive projects, with the Metropolitan Washington (DC) Council, for instance, sponsoring events all during the month of May and hosting regular walking tours. A network could tie together all these endeavors, connecting researchers and knowledge keepers from diverse settings. It could provide funding for new preservation and programmatic initiatives.

A network might also reveal what voices haven’t been documented, including stories that highlight discrimination and violence on the part of the labor movement – as well as against workers. A federal network might also prompt a more thorough and public analysis of the role of the federal government in shaping the trajectory of unions and other worker organizations. Scholars have published important work on connections between the state and labor, but this has not filtered down into historic sites and public interpretation to the degree that it needs to if we truly want to have a fruitful discussion about how labor has shaped the U.S. economy.

This idea is probably not novel. If it has been proposed before, please let us know what happened in the comments below. Or, if a network does not seem appropriate, what other means exist both to link together existing locations that tell labor movement stories and to call attention to worker histories of collective action more generally.

- See, for example, Rachel Donaldson’s article, “Placing and Preserving Labor History” in The Public Historian 39, no. 1 (2017): 61-83.