by Rolf Diamant

This article originally appeared in The George Wright Forum, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 107–111 (2014). It is part of a wide-ranging series of pieces, “Letters from Woodstock,” by the author.

I begin my eighth Letter from Woodstock by expanding upon a previous one (“Stewards of Our Heritage,” March 2013) that referenced preparations for the 2016 centennial of the National Park Service (NPS). In that Letter I suggested “broadening the emphasis beyond the parks themselves—to also highlight the many ways national parks and programs ‘preserve and support’ the well-being and aspirations of communities and people who use them.” I intentionally used the word broadening because an essential challenge facing NPS and almost all park and protected area systems is how to deliver high-quality public services and consistent stewardship but also be adaptable enough to remain relevant and responsive to the urgent needs and concerns of contemporary life. There is also a subtle shift in perspective: broadening a conversation that is often centered on what is best for the future of parks to a conversation that is expanded to include what is best for a larger set of social and environmental objectives and ways that parks, in collaboration with other institutions, can help achieve those objectives.

Former NPS Director Roger Kennedy spoke of the “usefulness” of national parks in the context, for example, of how they played an outsized role in emergency conservation, employment, and recreation projects during the Great Depression. The national park system also represented a popular national institution in a time of profound social demoralization. I would suggest that NPS continues to play a unifying role today in a country that seems pulled so in many different directions. The 2009 National Parks Second Century Commission Report described the national parks “as community builders, creating an enlightened society committed to a sustainable world.” The current National Park System Advisory Board, building on the National Parks Second Century Commission, articulates this higher purpose for NPS: “actively working to advance national goals for education, the economy, and public health, as well as conservation.”

I don’t take for granted (though I certainly won’t be around to see) that there will be a national park system to celebrate a third century in 2116. Though I am not inclined to either pessimistic or dystopian thinking, I have come to believe that nothing can be taken for granted; good work that has been done can also be undone. (As I write this, the Australian government, only a few months before the World Parks Congress convenes in Sydney, is repealing landmark legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.). NPS, like many other public institutions, will continue to be subject to a variety of stress tests, evaluating things like resiliency and adaptability, purpose and meaningfulness, ecosystem and cultural services, collaborative relationships, and their overall relevancy to what people care deeply about. That is why the work being undertaken by the advisory board and by a number of national parks and partner organizations to broaden the usefulness and relevancy of the national park system is so vitally important. Here are a few examples.

NPS, New York City, and a consortium of research institutions are using the Jamaica Bay unit of Gateway National Recreation Area as a living laboratory for testing new approaches for building climate change resiliency in urban coastal ecosystems. This is not the only place in the national park system where there is new thinking and research about climate resiliency, but given the devastation that Hurricane Sandy inflicted on the densely populated barrier islands of the metropolitan New York/New Jersey area, there is a particular sense of urgency to the Jamaica Bay project.

I have described in a previous Letter how the partnership between the Presidio Trust, NPS, and Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy is breaking new ground on integrating sustainable city living, historic preservation, and park design at the Presidio of San Francis- co, including the first national historic landmark property to be certified by the US Green Building Council as “LEED for Neighborhood Development” for “smart growth, urbanism and green building.” This ambitious re-purposing of vast military holdings for public benefit and use is only part of the story. Concurrent with this great transformation, an extraordinary bond is being forged between these national parks and people and communities of the San Francisco Bay Area, drawing the attention of park and protected area managers from all over the world.

On a very different scale, there is the interesting example of New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park’s Youth Ambassador Program (YAP!), a partnership project between NPS and Third Eye Youth Empowerment, a nonprofit dedicated to “building community and national pride through a series of learning experiences, skill development and real proj- ects … to improve the community, centered on the principles of economic and social equality.” The mission of the Youth Ambassadors is to “unite young people, utilizing Hip Hop, a common cultural art form and voice for the people, to engage and empower youth to positively change themselves and their community.” Working with New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, the Youth Ambassadors are producing a series of music videos, including their powerful hip-hop video “54,” about the 54th Massachusetts, the African-American regiment recruited by Frederick Douglass during the Civil War. The young performers infuse the narrative with their own distinct voice and message using an evocative, if unorthodox, interpretive format, making this compelling “Civil War to Civil Rights” story accessible to their friends and peers.

NPS is embarking on a landmark systemwide effort to develop what is being called an “urban agenda.” This urban agenda, is in part, an outgrowth of the 2012 conference titled “Greater & Greener: Re-Imagining Parks for 21st Century Cities,” organized by the City Parks Alliance in partnership with the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. An “affinity caucus” of NPS conference attendees, mostly from urban national parks, joined NPS Director Jon Jarvis to initiate an ongoing participatory process for identifying policy changes that will enable NPS urban parks and programs to “step into their power” with the intent of becoming a larger, more relevant part of urban life in America.

The scale of current NPS urban activities may come as a surprise to many people. Beginning in the early 1930s, Congress has gradually expanded the urban footprint of the National Park Service, establishing new units of the national park system in 40 of the country’s 50 most-populated metropolitan areas. Today, these national parks make up nearly one-third of the entire park system and draw approximately 40% of all national park users. The NPS National Capital Region and its 34 national parks in and around Washington, DC, for example, serve an urban population of more than five million people. Congress has also authorized more than two dozen different NPS programs providing urban communities with a wide range of services, including historic preservation tax credits, recreation grants, and conservation technical assistance.

Throughout this process of developing the urban agenda, the NPS Stewardship Institute (formerly the Conservation Study Institute) has been coordinating and documenting a series of webinar conversations with “communities of practice”—self-selecting groups of urban park practitioners—focusing on specific subjects such as urban innovation, economic revitalization, connecting youth to nature, and urban parks as portals for diversity. Attention tended to focus on what I might call “nuts and bolts” problems: how to streamline the use of legal authorities for leasing and cooperative agreements and how to align NPS funding and program priorities to concentrate available resources for greater impact. Lessons learned are shared for a variety of relatively new NPS-sponsored, community-based programs dealing with public transportation, safe routes to school, urban gardening, and partnerships with health providers. There is also an imperative to build a stronger “culture of collaboration” in which NPS operates as one partner among many. Underpinning all these discussions is the implicit vision of NPS as a “catalyst for civic renewal” consistent with the overall direction of Second Century Commission, the NPS director’s Call to Action, and the work of the National Park System Advisory Board.

The urban agenda is still very much a work in progress that will have to surmount competing interests and priorities, political jockeying, and bureaucratic inertia. There is also a danger that 2016 NPS centennial activities and a looming national election may, in effect, swamp it. There may also be internal resistance. Some may choose to interpret relevancy primarily in terms of making a fixed set of traditional park experiences more widely accessible rather than exploring ways to expand those experiences in order to engage a broader cross-section of the public (think “54”). Nearly 40 years ago, while I was working on the startup of the Golden Gate national parks, I clipped a Sierra Club Bulletin commentary by Jonathan Ela hammering NPS and other administraton officials for reversing previous support for urban national parks and testifying against making Cuyahoga Valley, located between the cities of Cleveland and Akron, Ohio, part of the national park system.

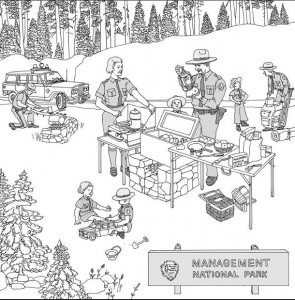

Contending that NPS personnel appeared at that time more comfortable with park users that looked and acted just like they did, Ela illustrated his article with this drawing by Steven M. Johnson (reproduced with permission of the artist).

Decades later, Bill Gwaltney (formerly with NPS—now with the Smithsonian), while working on diversifying the NPS workforce, would remind his colleagues that “people feel better [using parks] when they think their reality, their experiences, their culture, their expectations are on some levels mirrored in their national parks.”

National parks may also come to over-rely on their social media and marketing as substitutes for personal engagement and the patient hard work and risk-taking that builds trust and meaningful long-term relationships between parks and communities. Protecting parklands within clearly defined boundaries has always been a core function of the agency and it will no doubt be a challenge getting people to see an investment in “civic renewal,” particularly as budgets contract, as a central strategy for the long-term survival of national parks.

Even under the most favorable circumstances, moving an urban agenda forward will be difficult. There is a recurring concern that any reform, however desirable, might set a precedent that unintentionally provides an opening for parties with interests inimical to na- tional parks to do harm. Such concerns deserve careful consideration, and risk-taking must be judicious, yet the alternative of always playing it safe and resisting change has significant downstream dangers.

Let us hope that the newly established Urban Committee of the National Park System Advisory Board may be able to advance an NPS urban agenda, and, in the face of these obstacles, help sustain its momentum. Those working on the urban agenda understand that a system of national parks and programs that is perceived as being accessible, engaged, and resourceful will be a system that is ultimately valued, supported, and strengthened over time. This is what an earlier Advisory Board report, Rethinking National Parks in the 21st Century, envisioned when it advocated that parks reach “broader segments of society in ways that make them more meaningful in the life of the nation” and help build “a citizenry that is committed to conserving its heritage and its home on earth.”

A 21st-century agenda for urban national parks is, in many fundamental ways, an agenda for all national parks.

Rolf Diamant retired from the National Park Service in 2011, following a 37-year career with the agency. During that time, he developed new partnership models for national parks and conservation strategies for wild and scenic rivers and national heritage areas. He was the founding superintendent of the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park, in Woodstock, Vermont, as well as superintendent of Fairsted, the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site in Brookline, Massachusetts. He is currently an Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of Vermont