The ‘Long Paddock’ – the Heritage of Traveling Stock Routes in Australia

By Jane Lennon

In 1788, British convicts began to settle and colonize Australia and sheep numbers grew from the First Fleet’s cargo of 28 to well over a million by 1830, while cattle numbered about 370,000 by 1830. Because cattle were robust, mobile and adaptable to new environments, they were ideal as the stock-of-choice for new settlements. Their spread accelerated from the 1830s, while the wool industry developed transforming the economy into a mercantile trading one.

Pastoral expansion generated the trappings of settlement. Pioneer tracks soon became roads (the main ones built by convict gangs), and many are today’s highways. Villages established to service the local pastoral population became towns that still exist. The search for grass by pastoralists became the most important impulse for exploration across the continent for the rest of the century with the pastoral frontier expanding and contracting with the seasons.

Now that Australians mostly live in urban areas and close to the coast, the pastoral story is often forgotten. The rural way of life that saw Australia ‘ride on the sheep’s back’ until the 1960s no longer defines us; yet our life as a pastoral nation has endured in heritage places and is carried into the mythology of what it means to be Australian, our intangible cultural heritage.

In ecological terms it is not long since the first livestock were introduced to Australia but their impact has been profound in transforming many landscapes. Breeding livestock able to prosper in the Australian environment led to Australia quickly becoming, and remaining, the leading producer of fine fibre wool in the world.

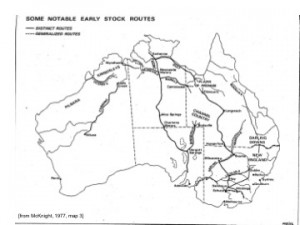

The countryside still bears the traces of the many droving routes to railheads and to metropolitan sale yards, wool stores, abattoirs, wharf facilities, railways, roads, and river and ocean transport systems. They were developed to link the pastoral interior, ‘over the ranges and far away’, with the urban and market infrastructure needed to distribute the pastoral products of sheep, cattle, wool, meat, skins and hides. They also served to take stock to pastures to improve the general condition of herds for breeding. Windmills, fences, homesteads, shearing sheds, bores, stock yards, travelling stock routes, bush tracks, roads and railheads all changed the look of the country. These features of our landscape, as much as the vast outback, are part of our heritage but they are poorly represented on heritage registers and local planning scheme overlays.

Traveling stock routes known colloquially as ‘the long paddock’ developed from the 1860s in all States and Territories. In some districts they used Aboriginal routes linking water supplies and in others, they developed new routes due to the availability of artesian water supplies. They still survive in current use in more remote parts of Australia – Queensland, western NSW and the Northern Territory and are used as four wheel drive routes for tourists especially the ‘grey nomads’. They also have a shared heritage with Aboriginal people whose country they crossed and who were employed often as stockmen and drovers until the 1970s.

The culture of droving and drovers featured large in the late nineteenth century development of a national identity through nascent Australian literature and art. In 2013 Tom Brinkworth organised a 2,500km drive of 18,000 cattle in nine mobs using 25 horses and 25 dogs moving 10km daily from parched north western Queensland to better watered lands in southern New South Wales emulating historic feats but on a larger scale. Metropolitan media reported regularly on this ‘epic odyssey’.

Australian stock routes are cultural routes, cultural landscapes with complex interconnected Indigenous and non-Indigenous heritage values, where cultural materials rarely occur in isolation. The routes tend to follow water courses – important cultural landscapes of long connection to Indigenous people, have intangible values from stories and knowledge attached to journeys and cultural practices and contain industrial heritage. The ‘long paddock’ is a uniquely Australian cultural route.

Thank you to Jane Lennon for authoring this month’s featured landscape.