To provide observations and information on the emerging fields of landscape scale conservation, heritage preservation, and sustainable community development.

Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the latest nature, culture and community news.

We won’t spam you or share your information. Newsletters are sent approximately 10 times a year. Unsubscribe at any time.

Outsized Threats to Large Landscapes

It should come as no surprise to readers of the Living Landscape Observer that conserving large landscapes in the current political climate is no easy task. There are threats to our public lands and proposals to defund the federal programs that conserve our cultural and natural resources. However, the bigger issue is the underlying erosion of landscape scale work throughout our national government. There are systemics challenges to all these efforts that need to be better understood.

From the Archives: Urban Recreation and Greenline Parks Capture Attention in 1975

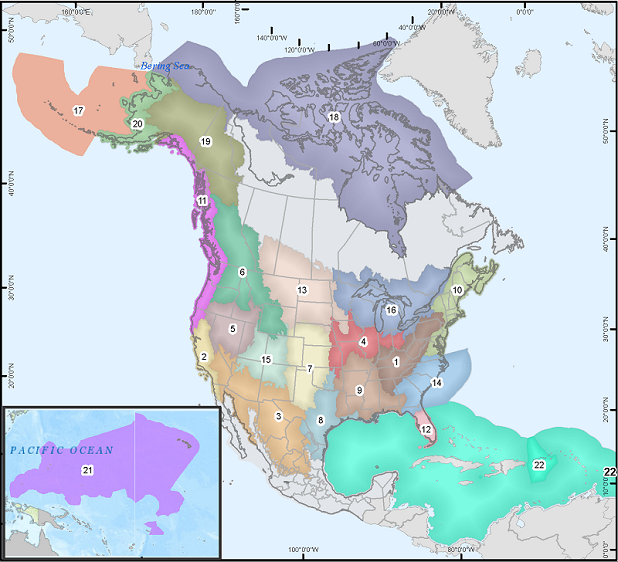

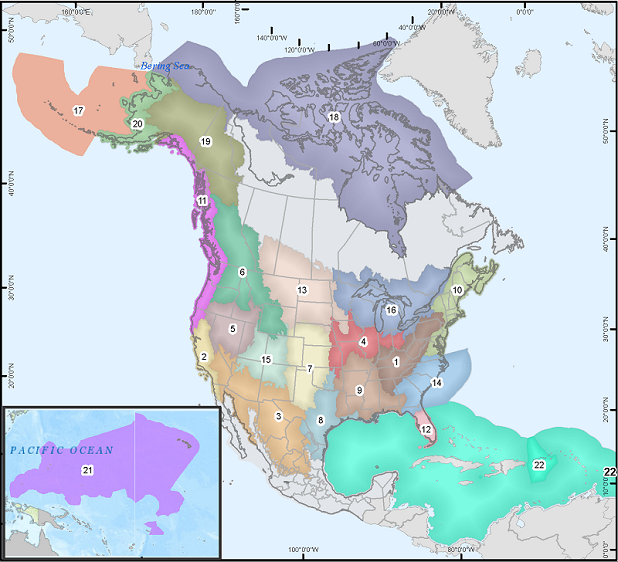

The mid 1970s proved to be a pivotal moment in the history of large landscape conservation. The funding boom of the sixties had come to an end, but the political influence of the environmental movement still held sway in many state capitols and in Washington, D.C. The administration of President Gerald Ford sought to cut back on federal investments in conservation, especially in cities, while members of Congress pushed for increases or – at the very least – preservation of the funding status quo. A document from the era, drafted by Charles Little of the Congressional Research Service, captures these tensions and is worth a read.

Featured Voice: Emily Bateson

In this month’s “Featured Voice,” we talk with Emily Bateson, the Coordinator for the Network for Landscape Conservation. She has more than 30 years experience in whole systems conservation, including projects that span the border between the U.S. and Canada.

Federal Budget: First Look is not Promising

On March 16, 2017 the Whitehouse released its budget framework styled America First: A Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again and the news was not great for programs that support large landscape conservation. For the FY 2018 the Department of Interior faces a proposed 12 % budget reduction and the Environmental Protection Agency is facing a 31% reduction. In general this brief document does not identify where the pain will fall except on the often pummeled National Heritage Areas. And while only the first step in the budget process, this proposal needs to be taken seriously.

Introducing the International Land Conservation Network (ILCN)

The need and the recognition of a growing movement inspired the founding of the International Land Conservation Network (ILCN), which is working to connect organizations and people across a broad spectrum of action relating to private and civic land conservation. The ILCN envisions a world in which the public, private, civic (NGO), and academic sectors, together with indigenous communities around the globe, work collaboratively to protect and steward land that is essential for wildlife habitat, clean and abundant water, treasured human historical and cultural amenities, and sustainable food, fiber, and energy production.

Outsized Threats to Large Landscapes

It should come as no surprise to readers of the Living Landscape Observer that conserving large landscapes in the current political climate is no easy task. There are threats to our public lands and proposals to defund the federal programs that conserve our cultural and natural resources. However, the bigger issue is the underlying erosion of landscape scale work throughout our national government. There are systemics challenges to all these efforts that need to be better understood.

From the Archives: Urban Recreation and Greenline Parks Capture Attention in 1975

The mid 1970s proved to be a pivotal moment in the history of large landscape conservation. The funding boom of the sixties had come to an end, but the political influence of the environmental movement still held sway in many state capitols and in Washington, D.C. The administration of President Gerald Ford sought to cut back on federal investments in conservation, especially in cities, while members of Congress pushed for increases or – at the very least – preservation of the funding status quo. A document from the era, drafted by Charles Little of the Congressional Research Service, captures these tensions and is worth a read.

Featured Voice: Emily Bateson

In this month’s “Featured Voice,” we talk with Emily Bateson, the Coordinator for the Network for Landscape Conservation. She has more than 30 years experience in whole systems conservation, including projects that span the border between the U.S. and Canada.

Federal Budget: First Look is not Promising

On March 16, 2017 the Whitehouse released its budget framework styled America First: A Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again and the news was not great for programs that support large landscape conservation. For the FY 2018 the Department of Interior faces a proposed 12 % budget reduction and the Environmental Protection Agency is facing a 31% reduction. In general this brief document does not identify where the pain will fall except on the often pummeled National Heritage Areas. And while only the first step in the budget process, this proposal needs to be taken seriously.

Introducing the International Land Conservation Network (ILCN)

The need and the recognition of a growing movement inspired the founding of the International Land Conservation Network (ILCN), which is working to connect organizations and people across a broad spectrum of action relating to private and civic land conservation. The ILCN envisions a world in which the public, private, civic (NGO), and academic sectors, together with indigenous communities around the globe, work collaboratively to protect and steward land that is essential for wildlife habitat, clean and abundant water, treasured human historical and cultural amenities, and sustainable food, fiber, and energy production.