Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area, Colorado

Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area, Colorado

Designated by Congress in 2009 (Public Law 111-11), the Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area in south-central Colorado encompasses approximately 3,500 square miles at the southern end of the San Luis Valley. Defined by the Sangre de Cristo Mountain Range on the east and the San Juan Mountain Range on the west, it includes the counties of Alamosa, Conejos, and Costilla, the Monte Vista, Alamosa, and Baca national wildlife refuges, and the Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve.

The heritage area was created for the broad purposes of promoting, preserving, protecting, and interpreting the region’s historical, religious, environmental, geographic, geologic, cultural, and linguistic resources. The Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area Board of Directors serves as the coordinating entity for the area and is leading the development of a management plan to be completed in 2012.

A wealth of stunningly beautiful natural resources and a rich mixture of Hispano and Anglo settlements converge within the heritage area to make it one of the most unique and well-preserved cultural landscapes in the nation. Snow-capped mountain peaks, the Rio Grande and its tributaries, forested hills and ancient volcanic mesas, thousands of acres of wetlands, and miles of hand-dug irrigation canals are but a few of the sights to behold. The most unusual may be the flock of sandhill cranes capping seasonal migrations of vast numbers of waterfowl and songbirds, and the national park’s enormous sand dunes, the nation’s highest, sustained by a unique cycle of wind and water above and below ground.

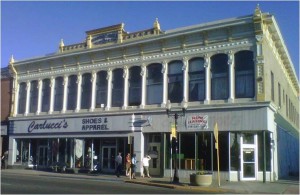

Well-known historic resources in the San Luis Valley include the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad and Fort Garland, where Kit Carson served as commander, today a state historic site. Less celebrated are vernacular Hispano resources, such as the historic plazas, acequias, placitas, moradas, churches, and cemeteries, and small-scale ranching and subsistence farming traditions. A branch of the Old Spanish Trail between Santa Fe and California is hardly visible on the landscape, its story only beginning to be told.

as commander, today a state historic site. Less celebrated are vernacular Hispano resources, such as the historic plazas, acequias, placitas, moradas, churches, and cemeteries, and small-scale ranching and subsistence farming traditions. A branch of the Old Spanish Trail between Santa Fe and California is hardly visible on the landscape, its story only beginning to be told.

Settlers from Mexico first arrived here in 1852 to found San Luis in the southeast corner of the area, the state’s oldest town. They brought with them Spanish traditions handed down from at least the 17th century, mingled with New World knowledge gleaned from interaction with indigenous American Indians. Dance, music, an archaic version of the Spanish language, foods, weaving, and embroidery are among the folk customs that enrich the Hispano culture (the preferred term here, not Hispanic or Latino).

Mormons settled in the valley later in the 19th century. Over succeeding decades more settlers followed from the eastern US, predominantly Swedes, Dutch, and Germans. Japanese from Pacific states were settled here during World War II. Quite recently, Amish farmers have begun migrating to the valley. The region’s rich modern cultural mix also includes many artists and a growing number of farmers and ranchers focusing on local foods amongst the irrigated fields of alfalfa and potatoes.

The valley’s high altitude means that the region’s newest wealth is found in the solar arrays beginning to dot the landscape. This process may be accelerated by the state’s restrictions on withdrawals of underground water for irrigation. Without this water, much of the land cannot be farmed, supporting only such desert vegetation as rabbitbrush and sagebrush.

The underlying land ownership patterns owe much to the terms of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War. Mexican landowners had held much of the region in extremely large land grants. Some held on to their land; others lost it in adversity, overwhelmed by American legal requirements. The Rio Grande National Forest, occupying much of Conejos County today, arose from extensive federal land acquisition at the turn of the last century. The same thing did not happen in Costilla County to the east, where owners more successfully defended their rights during that period.

In an irony belonging to the late 20th century, however, Conejos profits today from adjacency to the national forest, whereas Costilla’s remarkable community surrounding San Luis, still exercising common rights to land, has engaged in a bitter fight with landowners who closed off traditional access to the surrounding hills that offered forage and wood. Almost overnight after the closure in the 1960’s, families left the valley, never to return, or shifted from raising sheep to cattle, a profound change in the culture. Today, after a decades-long legal battle that has yet to end, those rights have been partially restored; the community now faces the challenge of teaching its children how to use them.

The stories of the people who lived here, their traditions and arts, and the evolution of this remarkable landscape and culture, moreover, are not evident to the visitor, nor even well understood by many residents. The heritage area has a rich opportunity to enhance interpretation through community involvement.

Based on the introduction to the Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area Management Plan, forthcoming, 2012. Courtesy HeritageStrategies, LLC, and the Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area Board of Directors.