To provide observations and information on the emerging fields of landscape scale conservation, heritage preservation, and sustainable community development.

Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the latest nature, culture and community news.

We won’t spam you or share your information. Newsletters are sent approximately 10 times a year. Unsubscribe at any time.

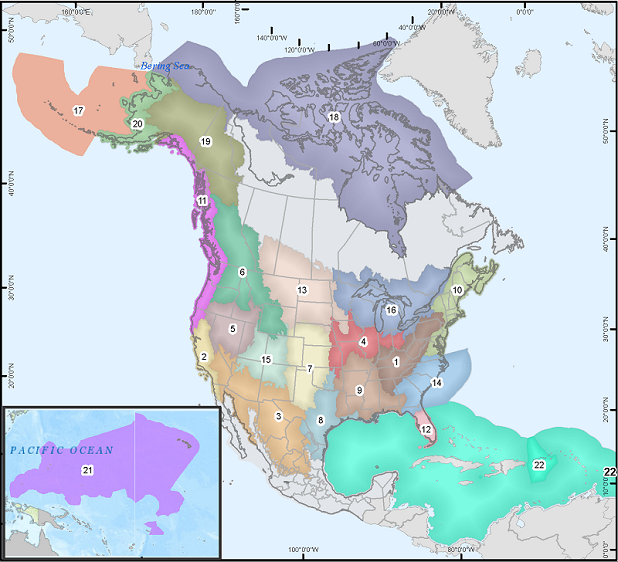

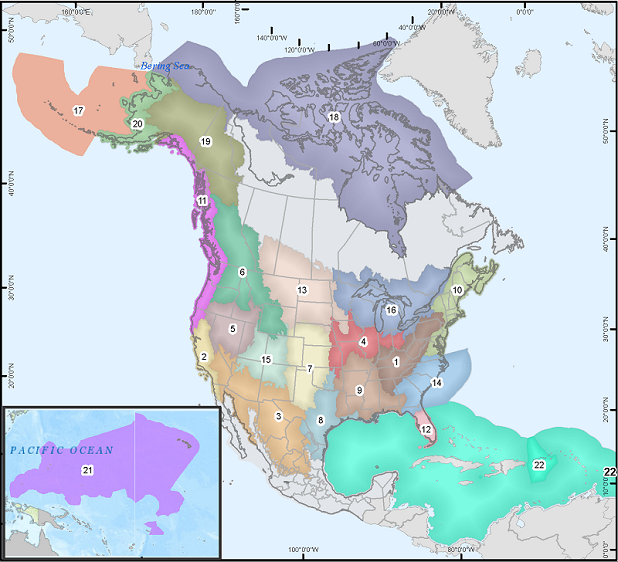

Outsized Threats to Large Landscapes

It should come as no surprise to readers of the Living Landscape Observer that conserving large landscapes in the current political climate is no easy task. There are threats to our public lands and proposals to defund the federal programs that conserve our cultural and natural resources. However, the bigger issue is the underlying erosion of landscape scale work throughout our national government. There are systemics challenges to all these efforts that need to be better understood.

The Nature Culture Journey continues: The Presidio in San Francisco

On November 13-14, 2018 US ICOMOS welcomed experts from 15 countries across six continents to a gathering at the Presidio in San Francisco. Titled Forward Together: Effective Conservation in a Changing World, the goal of the symposium was to share a range of ideas on how to integrate culture and nature and to explore ways to shape cultural and natural heritage for long-lasting conservation. Building on earlier international nature/culture journeys, the focus was taking action on the ground.

Protecting America’s Long Trails

October, 2018, marks the 50th anniversary of two remarkable federal laws: the National Trails System and Wild and Scenic Rivers Acts. Both laws set up ways that the federal government can assist in protecting and operating “long, skinny corridors” for recreation and heritage resource preservation. The key to the success of these corridors across the landscape and along our waterways has always been partnerships. Federal agencies working with private citizens and dedicated volunteers, have created irreplaceable links to our cultural and natural heritage.

Saving Spaces: Historic Land Conservation in the United States

In the latest featured voice, we interview Dr. John Sprinkle about his new book Saving Spaces: Historic Land Conservation in the United States. Dr. Sprinkle is an expert on the development of historic preservation in the United States. He has written widely on the effects of federal preservation policy on local, state, and national history. In this interview, we discuss the linkages and cleavages between historic preservation and environmental conservation as well as the often-times overlooked role of the Department of Housing and Urban Development in urban open space protection.

Interpreting histories of pollution

Do we need more historic sites that addresses the effects of pollution as well as remediation on the landscape. The Berkeley Pit in Butte, Montana provides one example of this type of location.

Outsized Threats to Large Landscapes

It should come as no surprise to readers of the Living Landscape Observer that conserving large landscapes in the current political climate is no easy task. There are threats to our public lands and proposals to defund the federal programs that conserve our cultural and natural resources. However, the bigger issue is the underlying erosion of landscape scale work throughout our national government. There are systemics challenges to all these efforts that need to be better understood.

The Nature Culture Journey continues: The Presidio in San Francisco

On November 13-14, 2018 US ICOMOS welcomed experts from 15 countries across six continents to a gathering at the Presidio in San Francisco. Titled Forward Together: Effective Conservation in a Changing World, the goal of the symposium was to share a range of ideas on how to integrate culture and nature and to explore ways to shape cultural and natural heritage for long-lasting conservation. Building on earlier international nature/culture journeys, the focus was taking action on the ground.

Protecting America’s Long Trails

October, 2018, marks the 50th anniversary of two remarkable federal laws: the National Trails System and Wild and Scenic Rivers Acts. Both laws set up ways that the federal government can assist in protecting and operating “long, skinny corridors” for recreation and heritage resource preservation. The key to the success of these corridors across the landscape and along our waterways has always been partnerships. Federal agencies working with private citizens and dedicated volunteers, have created irreplaceable links to our cultural and natural heritage.

Saving Spaces: Historic Land Conservation in the United States

In the latest featured voice, we interview Dr. John Sprinkle about his new book Saving Spaces: Historic Land Conservation in the United States. Dr. Sprinkle is an expert on the development of historic preservation in the United States. He has written widely on the effects of federal preservation policy on local, state, and national history. In this interview, we discuss the linkages and cleavages between historic preservation and environmental conservation as well as the often-times overlooked role of the Department of Housing and Urban Development in urban open space protection.

Interpreting histories of pollution

Do we need more historic sites that addresses the effects of pollution as well as remediation on the landscape. The Berkeley Pit in Butte, Montana provides one example of this type of location.