In 2016, the National Park Service will celebrate its 100th anniversary. If you work for or with the NPS, this is probably old news. However, for those outside of conservation and preservation circles, the information may well come as a surprise. Coverage of the upcoming NPS centennial in popular media has been relatively scarce, with prominent sources like the New York Times, Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, for example, devoting little coverage to the Agency’s plans for the upcoming year. What, if anything, does this relative lack of attention reveal about the current and future state of the NPS as well as its many affiliated programs and partnerships?

Fifty years ago, the NPS found itself in a radically different position – at least insofar as the media was concerned. As the country’s population exploded and as discretionary income and vacation time grew for many, though far from all, Americans, public lands, including National Parks, experienced an unprecedented surge in usage. At the same time, however, funding remained flat, resulting in overcrowded and even dangerous conditions at many sites. Popular magazines such as Life and Readers Digest published exposes on the subject. Among the most famous was a 1953 piece in Harpers by columnist Bernard DeVoto entitled “Let’s Close the National Parks.” In it, he critiqued both the entitled attitudes of many park visitors as well as the insufficient support provided by Congress.

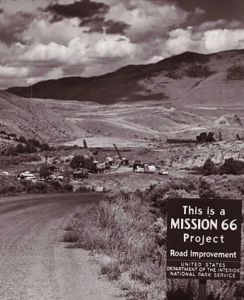

The article and others like it generated substantial interest in the future of recreation and land use, especially as it related to the park service. Within a few years time, the Agency would finally succeed in gaining the attention of decision makers in Washington, D.C., who approved a decade-long, multi-million dollar spending program dubbed Mission 66, which aimed to “modernize” the parks in time for the NPS’ 50th anniversary in 1966. The initiative received substantial attention in the press, with numerous articles in local and national publications highlighting efforts big and small.

In the end, Mission 66 fundamentally re-oriented the way visitors experienced NPS units, whether through the addition of new front country amenities, the building of enlarged visitor centers or the construction of new roadways to previously inaccessible areas. These projects and others proved controversial, with many scholars crediting Mission 66 as a factor driving support for passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964 as well as a push against commercialization in NPS units.

Roughly a month ago, on September 1, 2015, Interior Secretary Sally Jewell announced the Obama Administration’s legislative proposal for the upcoming NPS centennial. Dubbed the National Park Service Centennial Act, the bill focuses particular attention on the creation of a Challenge Fund, which would use both private and public monies to support “signature projects.” In addition, a separate, smaller Public Lands Centennial Fund would also be established, which would provide up to $100 million annually to not only the NPS, but also other federal land or water management agencies, including the Bureau of Land Management, the Bureau of Reclamation, the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Forest Service. Attention in the bill is also focused on youth outreach, volunteers in parks, interpretation and visitor services. But, what is the big picture or vision behind this initiative? It’s hard to tell. What does the Agency want to become over the next 50 or 100 years? For all its shortcomings, which were myriad, Mission 66 captured the public’s (albeit a select public of park goers) imagination. Will this effort do the same? Are public-private partnerships the answer to the NPS’ chronic under-funding? Do new approaches to large landscape management need to get more attention? What do you think?