By Rolf Diamant

* this article originally appeared in the The George Wright Forum, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 271–274 (2016)

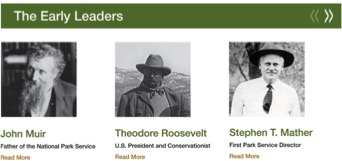

In 1903, Theodore Roosevelt insisted on camping alone with John Muir while the president was on a tour of Yosemite. This encounter no doubt encouraged Roosevelt to support the eventual inclusion of Yosemite Valley into the larger Yosemite National Park. With the 2016 National Park Service (NPS) commemorations winding down, I took another look at the agency’s centennial webpage where there is a special feature with the biographies of “early national park visionary leaders.” Muir and Roosevelt are there, reunited once again and given top billing as the lead visionaries of the national park movement, along with Stephen Mather, the politically adroit and charismatic first NPS director.

They are all credited with “groundbreaking ideas preserving America’s treasures for future generations,” with Muir praised as “the father of national parks.”

Roosevelt was of course a great conservation-minded president and Muir was a brilliant publicist and a passionate and influential park and wilderness advocate. However, national parks had already been in existence for more than 30 years at the time of the camping trip, and the establishment of a National Park Service would not happen until 1916, 13 years later, when Roosevelt had long been out of office and John Muir was dead. What is most striking about this official web feature is not only who is being given all the credit but also who is being erased, in effect, from this high-profile NPS history lesson.

To begin with, there is no mention of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and his landmark Yosemite Report, or of his son, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who penned the compelling statement of purpose for the 1916 Organic Act. The elder Olmsted’s 1865 park plan for Yosemite Valley presciently called for the “establishment by government of great public grounds for the free enjoyment of the people”—a prescription for a future system of national parks. There is no mention of Congressman John Lacey, principal sponsor of the 1906 Antiquities Act, which has been referred to by historians as the first national park service “organic act.” And there is no mention of J. Horace McFarland, long-time leader of the American Civic Association, who was the driving force behind 16 bills introduced into Congress to establish a national park service. Neither is there any mention given to Mary Belle King Sherman, also known as “the national park lady,” who mobilized 3,000 clubs and nearly one million mem- bers of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs behind McFarland’s campaign. Looking years into the future, Sherman envisioned the contributions national parks would make to American civic life and education, asserting that they provide “the better, greater things of life” possessing “some of the characteristics of the museum, the library, the fine arts hall, and the public school.”

Part of this official adulation of John Muir, as “the father of national parks,” is, I suspect, in part due to his larger-than-life popularity with contemporary environmentalists and wilderness enthusiasts. The fabled Roosevelt–Muir encounter was also a story made for television. In 2009, Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan obliged, devoting part of an episode of their documentary series on national parks to the Muir–Roosevelt camping trip in Yo- semite—further canonizing the two, in the public’s eye, as the main architects of “America’s best idea.” NPS has made little official effort in the centennial to present a more inclusive, scholarship-based narrative. This has been a recurring problem for the agency. For much of the 20th century NPS clung to a story, discredited by its own historians, that the national park idea was first suggested by explorer Cornelius Hedges seated around a campfire in the Yellowstone wilderness. A high-level NPS official once said, when scholars challenged the story, “If it didn’t happen we would have been well advised to invent it.”

In the case of the 2016 centennial web page, I am not questioning the very significant contributions Muir, Roosevelt, and Mather made to conservation and national parks, but the story being told is too neat and woefully incomplete. This was just what the Organization of American Historians’ report Imperiled Promise: The State of History in the National Park Service, issued in 2011, five years before the centennial, cautioned NPS to avoid: interpretation that is “less the product of training and expertise and more the expression of conven- tional wisdom.”

I think the inclusion of Olmsted (and, for that matter, his son, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.), Lacey, McFarland, and Sherman could have in fact strengthened the overarching themes of the 2016 centennial campaign in a number of helpful ways:

Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr.—forcefully argued that the concept of protecting special places for the benefit of all people, not only privileged groups, has always been an idea worth fighting for. His example suggests that meaningful change arises from an engaged citizenry and the duty of government, based on principles of “equity and benevolence.”

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.—called for an agency with the highest ethical and profes- sional standards and understood and consistently promoted the advantages of a strong and unified system of national parks.

Congressman John Lacey—made profound contributions to American conservation and reminds us all that NPS cares for places with multiple values and layers of meaning. In our current era of scaled-up landscape conservation, there are lessons to be learned from the way Lacey brought natural, scientific, cultural, spiritual, recreational, and eth- nographic interests together in a big conservation tent.

J. Horace McFarland—repeatedly emphasized that public lands are the heritage of all Americans and are essential to the health and well-being of our democracy; or, as he said, “a plain necessity for good citizenship.”

Mary Belle King Sherman—clearly saw how central to continuous life-long learning national parks could be, and how education and civic engagement have always been a fundamental purpose of public land stewardship.

A 2016 election postscript

The results of the recent election mean there will likely be hard times ahead for America’s national park system. Park supporters everywhere will have to resist the temptation to retreat into a defensive posture solely focused on protecting park resources and budgets while putting aside or perhaps abandoning our highest aspirations for the future of the national park system. Though many difficult and painful battles over resources and budgets may lie ahead, there are higher purposes for the system also at stake—a broad vision that had its roots with people like the Olmsteds, Lacey, McFarland, and Sherman. It is a vision that has been refined and expanded by several incarnations of the National Park System Advisory Board since the 2001 John Hope Franklin report, by the careful work of the 2009 National Park Second Century Commission, and by the 2016 NPS/National Park Foundation centennial campaign that is now concluding. This is a vision of a national park system that is inclusive and committed to engaging diverse constituencies in cooperative stewardship and life-long, real-world learning. It is a vision that always embraces the best current science and scholarship. It is a vision that values national parks and programs for their many contributions to climate resiliency, to ecosystem services, and to the public health and well-being of the nation.

It is a vision we have to hold on to.