To provide observations and information on the emerging fields of landscape scale conservation, heritage preservation, and sustainable community development.

Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the latest nature, culture and community news.

We won’t spam you or share your information. Newsletters are sent approximately 10 times a year. Unsubscribe at any time.

2013: Let’s Meet Up on Living Landscapes

Mitigation: Now thinking on a Landscape Scale

Why is Funding Large Landscape Work so Darn Hard?

The major land and water conservation challenges facing the nation require action on a scale that is large and multi-jurisdictional.The benefits of landscape connectivity are resilient habitats, essential ecosystem services and stronger cultural connections. Yet, generating and sustaining funding for efforts that seek to work on a landscape scale remain daunting. Why is this case and what might be done about it?

Economic Change and Park Policy

Political economy has long shaped park policy in the United States. Beginning in the late 19th century when the booming railroad business drove the designation of new National Parks to more recent shifts towards privately-funded public spaces, protected areas have always reflected the dominant economic ethos of an era. What can we learn about post World War II park-making by looking at the changing role of the state and the increasing mobility of capital during that time period?

Twitter Tips

Some great twitter tips to consider when utilizing your social media accounts from the manager of the @landscapeobserv twitter account.

Biosphere Reserves: A Second Chance for the United States?

Biosphere reserves serve as special places for testing interdisciplinary approaches to understanding and managing changes and interactions between social and ecological systems, including conflict prevention and management of biodiversity.

However, for many years now the biosphere reserve program in the US has been dormant. Learn about new efforts to re-invigorate the initiative.

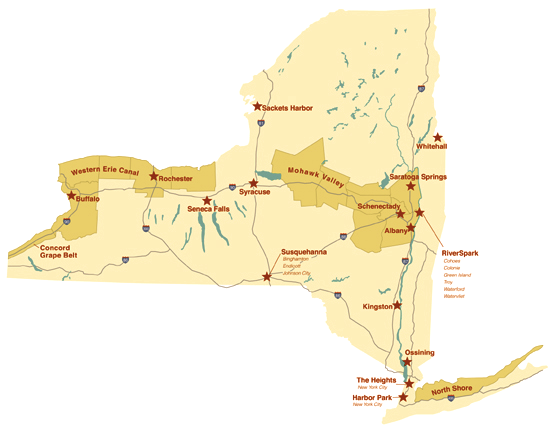

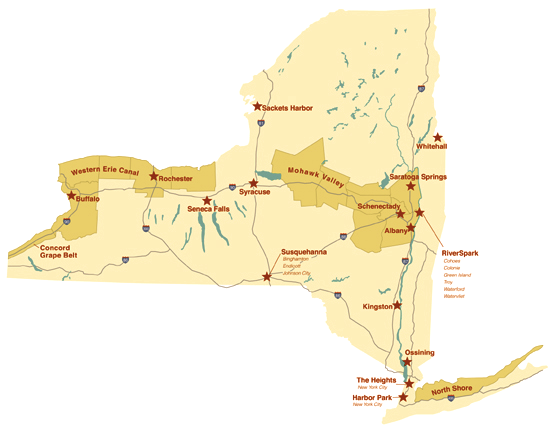

New York State Parks: Funding Heritage Innovation

Urban cultural parks and heritage areas have a history that now dates back almost four decades, yet they often still struggle to receive adequate and predictable support at the local, state and federal levels. Why do programs so often touted as the future of conservation and preservation receive so little support from agencies and public officials charged with managing their funding?

Why is Funding Large Landscape Work so Darn Hard?

The major land and water conservation challenges facing the nation require action on a scale that is large and multi-jurisdictional.The benefits of landscape connectivity are resilient habitats, essential ecosystem services and stronger cultural connections. Yet, generating and sustaining funding for efforts that seek to work on a landscape scale remain daunting. Why is this case and what might be done about it?

Economic Change and Park Policy

Political economy has long shaped park policy in the United States. Beginning in the late 19th century when the booming railroad business drove the designation of new National Parks to more recent shifts towards privately-funded public spaces, protected areas have always reflected the dominant economic ethos of an era. What can we learn about post World War II park-making by looking at the changing role of the state and the increasing mobility of capital during that time period?

Twitter Tips

Some great twitter tips to consider when utilizing your social media accounts from the manager of the @landscapeobserv twitter account.

Biosphere Reserves: A Second Chance for the United States?

Biosphere reserves serve as special places for testing interdisciplinary approaches to understanding and managing changes and interactions between social and ecological systems, including conflict prevention and management of biodiversity.

However, for many years now the biosphere reserve program in the US has been dormant. Learn about new efforts to re-invigorate the initiative.

New York State Parks: Funding Heritage Innovation

Urban cultural parks and heritage areas have a history that now dates back almost four decades, yet they often still struggle to receive adequate and predictable support at the local, state and federal levels. Why do programs so often touted as the future of conservation and preservation receive so little support from agencies and public officials charged with managing their funding?