By John H. Sprinkle, Jr.[i]

“The family farm is sacred ground:” so opined Tiffany Dowell Lashmet in the April issue of Progressive Farmer.[ii] This often repeated and widely felt sentiment is well understood and broadly accepted among families who have generations of attachment to a particular patch of ground. It has inspired many, both farm owners and land conservation advocates, to develop creative secular ways to protect spaces and places that are held dear, and that represent a physical gift to future generations.

A common means to provide for the perpetual conservation of a family farm, or any historic resource, is the legal instrument known generally as a conservation easement.

In Maryland farmland preservation has a long history. It developed in relation to efforts to preserve the viewshed from George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate across the Potomac into Prince Georges County during the late 1950s and early 1960s.[iii] In 1966 Maryland was the first state to authorize the differential taxation of parcels encumbered with conservation easements, an approach that enhanced the value of such easements as a landscape conservation tool.[iv]

National recognition for this achievement was evidence by NPS Director George Hartzog’s presence at the Annapolis signing ceremony for the “scenic easement bill” in May 1965 and Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall’s participation at the January 1966 ceremony marking Prince George’s County’s adoption of a conservation easement program.[v] At that time, such easements were seen as just the right prescription to address the ever increasing acquisition costs for those portions of the rural landscape thought to be worthy of protection then and into the future.

With increasing suburbanization in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s (fostered by federal housing loan programs and further development of the interstate highway system) conservationists and political leaders in Maryland’s rural communities began to recognize the loss of prime farmlands as a threat to the economic and cultural survival of farming within the state.

The Maryland Agricultural Land Preservation Foundation (MALPF) was established by the General Assembly in 1977, three years before the creation of the American Farmland Trust (AFT), a nationwide organization that highlighted diverse threats to the continuation of farming in the United States, as well as efforts to conserve such landscapes.

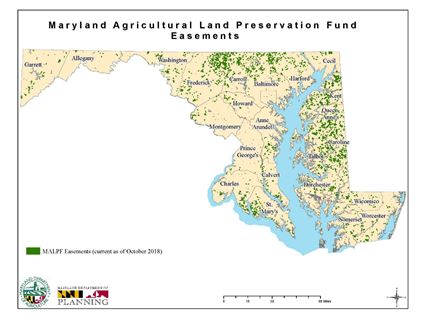

Using easements as a conservation tool, MALPF acquired its first agricultural land preservation easement in 1980. By 2017, the MALPF program had expanded to include the permanent protection of more than 300,000 acres spread across more than 2,200 farms in the state. Through a variety of federal, state, and local land conservation programs, Maryland has permanently preserved more agricultural land than any other state.[vi]

Beyond these impressive statistics is the recognition that placing a conservation easement on a property is in itself a historic act. I can vividly recall the family meeting, held around the kitchen table, where my parents discussed participation in various land conservation programs. It was in 1987, during the bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution, and our place had been recognized as one of 30 “Bicentennial Farms” in Maryland by the United States Department of Agriculture for its status as a family farming operation for over two centuries.

That same year, as evidence of their commitment to the conservation of the farm’s cultural landscape, my parents entered into a “district agreement” with the MALPF program. With this agreement, they committed to preserving the farm and maintain its agricultural land uses for a five year period, an action that set the stage for a subsequent execution of a permanent easement on the property in 2004. Efforts to conserve—in perpetuity–the cultural landscape within this property constituted a significant event in the history of its land use.

But when does the act of conservation itself become historic? Among the federal lands, there are at least two examples where parcels are automatically considered as being eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places: at National Parks and National Cemeteries. From the moment these places are created, that is, placed into perpetual federal care by the Congress, they are considered as historic properties and are afforded the protections found within the National Historic Preservation Act and other federal statutes.

In the same way, farm lands that are protected via a perpetual conservation easement are immediately historic places. The permanent nature of the easement means that its impact on the property’s land use history will be no more significant in five, ten, or even 50 years.

By definition, the act of establishing a permanent easement is an exceptionally important event, and worthy of consideration and enumeration within the National Register—no so-called “50 year rule” need apply to these properties. Acknowledging the secular significance of conservation easements, many states have invested considerable funds to identify, evaluate, and support the continuing stewardship of what Lashmet called “sacred ground.”

From a cultural landscape perspective, the act of establishing a permanent conservation easement creates a historic property. Such an approach would have two potential impacts: first, land conservation advocates would be able to characterize the execution of a permanent easement as a historically significant act—one that tied today’s actions with those in the past and in the future.

Second, the landscape of historic properties within agricultural communities would gain another layer of recognition, in that parcels protected by perpetual easements, now considered as historic properties in their own right, would gain additional consideration during future planning endeavors by local, state, and federal agencies. The former Executive Director of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Robert Garvey was correct when he observed in 1969 that both “the act of preservation and the product preserved are a part of a meaningful life and meaningful total environment.” [vii]

John H. Sprinkle, Jr. is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of Maryland School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation and serves as a historian for the National Park Service. He has published widely on the history of the historic preservation and land conservation movements. He and his wife, Esther, are stewards to a legacy family farm on Maryland’s Eastern Shore which in 2014 completed its third century of operation.

[i] The views and conclusions in this essay are those of the author and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the National Park Service or the United States Government.

[ii] Tiffany Dowell Lashmet, “This is Sacred Ground,” Progressive Farmer, (April 2019), pg. 11.

[iii] John H. Sprinkle, Jr., Saving Spaces: Historic Land Conservation in the United States, (New York: Routledge, 2018), pp. 23-43 and 150-151.

[iv] “The Nation’s First Local Law Granting Tax Credits for Preservation,” Preservation News, February 1, 1966.

[v] Richard Homan, “Prince George’s Passes First Law in U.S. To Exchange Tax Credit for Open Space,” The Washington Post, January 16, 1966.

[vi] The Maryland Agricultural Land Preservation Foundation FY2017 Annual Report.

[vii] Robert Garvey, “Look Back in Anger?” Preservation News, February 1, 1969.