By Lisa Bergstrom

In the summer of 1619 a Spanish ship, the São João Bautista, was enroute to New Spain (Mexico) from a Portuguese outpost on the west coast of Africa. The ship was carrying 350 enslaved Africans, probably people from the kingdom of Ndongo. Records reveal the ship did not make it to New Spain without incident and it is estimated 150 of the enslaved souls died enroute and another 50 were stolen by English privateers (on two ships) in the Gulf of Campeche, off the coast of New Spain.

By late August, the first ship, The White Lion , arrived at Point Comfort, Virginia on the James River. John Rolfe wrote a letter describing the captain and his cargo: “ He brought not any thing but 20. and odd Negroes, which the Governor and Cape Marchant bought for victualls (whereof he was in greate need as he pretended) at the best and easyest rates they could” (Encyclopedia of Virginia, 2012). The “20 an odd” – historians now believe as many as 32 – enslaved people were sold again, some, or all of them were taken to Jamestown. We know that one woman was called “Angela or Angelo” and purchased by Lieutenant William Pierce and 8 others became the property of the Governor. Sir George Yeardley.

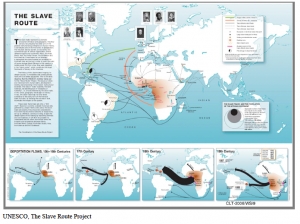

Sometimes called the “triangular trade” the main players in the transatlantic slave trade were Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, England and France, and involved Africa, America, the Caribbean, Europe and the Indian Ocean. The route took about 18 months and followed three basic steps:

1. Ships from Western Europe sailed to Africa with goods to trade for slaves

2. The ships then crossed the Atlantic where the enslaved were sold

3. The ships sailed for Europe carrying products produced in America (sugar, cotton, coffee, tobacco and rice)

Angela, and all those like her, who remain nameless, were stolen from their homeland and forcibly brought across the Atlantic to America. Theirs is a story of horror and survival. The beginnings of what would become an economic machine, sometimes referred to as the first system of globalization (UNESCO). The Jamestown example is an excellent look at how many countries were involved and how they benefited. Africans, “ the governor of Angola, Luis Mendes de Vasconçelos, fighting alongside a ruthless African mercenary group called the Imbangala, led two campaigns against the Kimbundu-speaking people of the region” (McCartney, 2017). Portuguese, who had established thriving slave ports off the west coast o f Africa (and who are responsible for sending as many as six million men, women and children across the Atlantic from the 16th-19th centuries), the English who would steal the valuable cargo under the protection of the Dutch who would issue them a “letter of marque” making them privateers instead of pirates, and the Dutch who benefit from the actions of the privateers.

On the first page of The Slave Route Project you will find this quote:

‘We acknowledge that slavery and the slave trade, including the transatlantic slave trade, were appalling tragedies in the history of humanity not only because of their abhorrent barbarism but also in terms of their magnitude, organized nature and especially their negation of the essence of the victims, and further acknowledge that slavery and the slave trade are a crime against humanity’ Declaration of the World Conference against Racism (Durban, 2001, Paragraph 13).

In March, 2018 an international conference was held at the University of Virginia on “Interpreting and Representing Slavery and its Legacies in Museums and Sites: International Perspectives” . This conference, sponsored by Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, the University of Virginia , and the United States Committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites along with the United National Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization Slave Route Project: Resistance, Liberty, and Heritage brought together scholars and professionals from four continents.

This remarkable gathering highlighted the work that has been done across the world to tell a more transparent and truthful history of the transatlantic slave trade as a transnational cultural landscape. It brought to light the many resources available to cultural heritage professionals as well as pushing for further conversation, research and understanding. Currently, The Slave Route Project lays out the following topics for Nation States to act upon:

● Memory, shared history and heritage

● Interculturality, transculturality and new forms of identity and citizenship

● Human rights, fight against racism and discrimination, new solidarities and new

humanism

● Africa and its diasporas past and present

● Living cultures and contemporary artistic creation (depiction and staging of slavery)

● Intercultural education, culture of peace and intercultural dialogue.

And, what about Angela? Historic Jamestowne, in conjunction with the National Park Service is working to uncover (literally) her story and the stories of the enslaved on the island. The Angela Project involves Jamestown Rediscovery’s archaeology program. “ The current Jamestown Rediscovery excavations that began in 2017 and are expected to continue for three years. Goals for the project go well beyond locating the Pierce home site, identifying its occupants, and determining how the site evolved. They hope to intensively examine Angela’s impact on the Pierce family—the earliest known record of an enslaved African living in a household in English North America—to learn more about race, ethnicity, and inequality across the plantation landscape of 17th-century Virginia” (Jamestown Rediscovery, 2018).

The Slave Route Project is a vast and complex cultural landscape, and there has been much research on the scope and scale of the four centuries of the slave trade. But, go beyond the large landscape, cultural heritage professionals should not hesitate to look for the humanity that can be found in the telling of individual stories, like Angela.

References

Historic Jamestowne, n.d., The First Africans , Retrieved from https://historicjamestowne.org/history/the-first-africans/

National Park Service, 2015, African Americans at Jamestown , Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/african-americans-at-jamestown.htm

McCartney, Martha, 2018, Virginia’s First Africans , Retrived from

https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Virginia_s_First_Africans#start_entry

Rolfe, John, 1619, ” 20. and odd Negroes “; an excerpt from a letter from John Rolfe to Sir Edwin Sandys, 2012 The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 8. Virginia Records Manuscripts. 1606– 1737. Susan Myra Kingsbury, ed., Records of the Virginia Company, 1606–1626 , 3:241–242, 243–245, 247–248, Retrieved from

https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/_20_and_odd_Negroes_an_excerpt_from_a_letter_from_John_Rolfe_to_Sir_Edwin_Sandys_1619_1620

UNESCO, n.d., Transatlantic Slave Trade , Retrieved from

http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/slave-route/transatlantic-slave-trade/

UNESCO, n.d., The Slave Route , Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/slave-route/

Vanderbilt University, 2018, Slave Societies Digital Archive, Angola , Retrieved from https://www.vanderbilt.edu/esss/angola/index.php

Cottman, Michael, 2017, ‘Angela Site’ Uncovers Details on one of first enslaved Africans in America , Retrieved from

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/angela-site-reveals-daily-life-enslaved-african-american825701

Lisa Bergstrom is the Preservation Programs Manager for Preservation Virginia. She works with communities around the commonwealth to help identify, preserve and advocate for their cultural heritage resources. Her current work includes advocacy for the cultural resources in the City of Petersburg, a survey of Virginia’s Rosenwald Schools, historic African American cemeteries and exploring the significant story of diversity at Historic Jamestowne. She is currently pursuing her MA in Cultural Heritage Management with Johns Hopkins University.