Credit: Ariel Schnee

When I was growing up in the suburbs outside of Detroit in the early and mid-1990s, it was easy to forget that the city existed. Generally speaking, if you were white, you didn’t go downtown. Even on the odd occasion that you found yourself in the city, you didn’t hang around, and you definitely left before dark. Detroit is a place indelibly marked by the highest highs and the lowest lows of American history. Its crumbling buildings and forgotten factories are the tangible evidence of economic booms and busts, the rise and decline of American manufacturing, and the after-effects of WWII, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, racism and classism, as well as decades of local mismanagement and corruption.

In Detroit, hope and resilience, despair and neglect, are not only inscribed upon the landscape, they are often next-door neighbors. Over the years, I saw family and friends steadily abandon their homes around the city as their neighborhoods went “bad.” In the 1990s, and even now, Detroit was a hard place to love, and an even harder one in which to live. But Detroit is also so much more than the disaster porn the media likes to show, and the city has a weirdly magnetic attraction. Some insanely determined people do, in fact, live in Detroit, and they do incredible things there—Detroiters create art, perform and record cutting-edge music, and work at the very forefront of urban agriculture. The people who have managed to remain there literally make the city bloom around them. But regardless of their incredible accomplishments and tenacity, it is a sad truth that, since the advent of white flight from urban America in the 1960s, almost anyone who was able to go somewhere other than Detroit, did. The wealthier and whiter you were, the further you went, and you never looked back.

And that was why I was sitting at a desk in Colorado, and not one in Michigan, when the notice for the George Wright Society’s 2016 Park Break appeared in my email inbox. When I saw that the program was taking place in Detroit, I knew I had to seize the chance to go back, so I applied. Park Break is a week long program for graduate students to gain experience working on public lands, usually in National Parks. Park Breakers normally work on a defined project and are supported by the hosting park’s staff and resources.

Courtesy: Lorin Brace

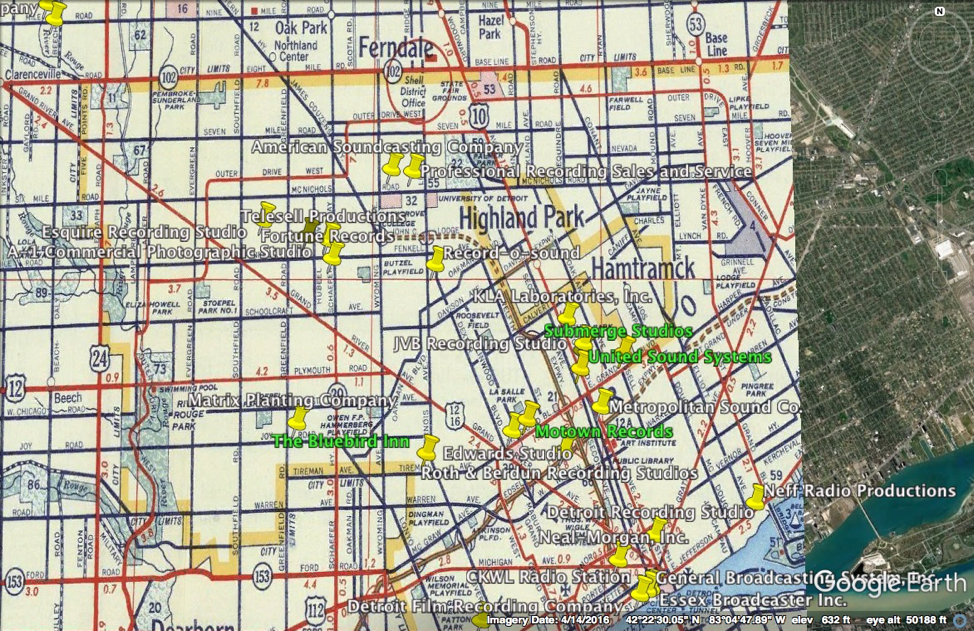

Despite the amount of NPS tax breaks and grant money invested in rehabilitation projects in Detroit, there was no national park we could rely on to help us in our work. As an NPS Urban Fellow, Dr. Goldstein was looking for a way to implement the NPS Urban agenda—an NPS program aimed at making parks more relevant and accessible to urban populations—in Detroit (for more information on the Urban Agenda, click here). Dr. Goldstein created the Park Break in order to lay the research basis for a full National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) district nomination that highlighted Detroit’s longstanding importance to musical history in America. The need to preserve these buildings is pressing. Detroit is currently experiencing a burst of revitalization centered on the downtown area. Nearby neighborhoods are redeveloping quickly, but often haphazardly, and in ways that threaten historic buildings and neighborhoods.

Without a park home base, we pieced together the project from the resources that were available in the community. We borrowed workspace at Wayne State University, research materials from the Burton Library’s Special Collections and the Detroit Historical Society, and expertise from local music authorities and the property owners themselves to try and reconstruct the history of four of Detroit’s most important musical heritage sites. In partnership with Wayne State University and the City of Detroit, Dr. David Goldstein identified the Bluebird Inn, Motown Records, United Sound Systems and Submerge Studios as candidates for an NRHP historic district.

Courtesy: Google Earth

Each property represents a distinct element of Detroit’s musical heritage. The Bluebird Inn was a popular African-American nightclub and the birthplace of Bebop, a highly energetic and improvisational form of Jazz. Motown Records was home to Berry Gordy’s “Empire on West Grand Boulevard,” where musical legends like Diana Ross, Marvin Gaye, and Martha and the Vandellas made timeless Motown hits. Though it has changed hands several times, United Sound Systems remains to this day a professional recording studio, and famous musicians like John Lee Hooker and the Motor City 5 made music at United Sound Systems ranging from Blues to Punk Rock. Submerge Studios represents yet another musical genre born in Detroit—Techno. The building was once used as a union gathering place. Today, the historic building houses a Detroit techno music label, radio station, and recording studio.

The buildings themselves reflected the full range of conditions one might find in Detroit as a whole. The Bluebird Inn, for example, has sat vacant in a rough neighborhood for fifteen years. It lacks doors and a complete roof, and is in an advanced state of decay. United Sound Systems, while well-maintained, is currently under threat of eminent domain from a proposed highway expansion. Motown Records and Submerge Studios are not under threat, but should be recognized on the National Register due to their integrity and historic significance to Detroit’s musical heritage.

The buildings we examined were the survivors of a formerly broad and dense network of recording studios, radio stations, record stores, and talent agencies . African American musicians, recording artists, and entrepreneurs created economic opportunity in their own neighborhoods that the outside world often denied them. Banks refused to approve African Americans for commercial loans on the basis of their race. Even if African Americans had business capital through other means, racist city zoning practices, or “red lining,” made buying property outside of certain neighborhoods was nearly impossible. To start their businesses, Black Detroiters got creative, borrowing money from family and friends, and setting up fledgling recording studios in non-commercial spaces, like private residences. From their homes, Berry Gordy (founder of Motown), James Siracuse (the North African founder of United Sound Systems) and other African American entrepreneurs created, captured, and distributed a timeless sound that was assertively Black and distinctively Detroit.

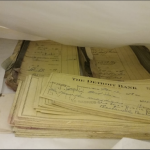

Although not yet an official historic district, the spatial arrangement of the Bluebird Inn, Motown Records, United Sound Systems, and Submerge Records are physically grouped so closely to one another that regarding them holistically as a historic district was natural and intuitive. However, a lack of sources remains a barrier to any future NRHP nomination. Because businesses and studios changed hands frequently, many of the records necessary to prove the sites’ historic significance are now lost, and development now threatens their historic integrity. Under-funding of cultural institutions like the Detroit Public Library also means that while the library has retained its collections, much of the research infrastructure is under-developed. For example, the library still relies on a physical card catalog, which makes the research process slow and laborious by the digital age’s standards. Thanks to Wayne State University’s recent archaeological investigation of the Bluebird Inn, the building has yielded a forgotten cache of documents, including receipts, pay stubs, and other invaluable historic evidence. The collection now resides at Wayne State University and is the subject of an Archaeology Master’s thesis by Wayne State University student and 2016 Park Break participant, Lorin Brace .

Apart from the four sites we researched as part of Park Break, we do not know how many of the buildings where other African-American owned music businesses once operated still exist. Hundreds of African American-owned businesses in Detroit’s Black Bottom and Paradise Valley neighborhoods were demolished to make way for the I-75 highway as part of an urban renewal project. Most of the former residents relocated to public housing, such as the Brewster projects, to the profound detriment of Detroit’s African-American community.

Over the course of that whirlwind week in Detroit with Park Break, I got to see the city as it enters a new phase, one that, shockingly enough, includes breweries, artisanal coffee shops, trendy restaurants, and high-end watches. While it was thrilling to see the city coming alive for the first time in my lifetime, Park Break was also an opportunity for my team and me to think seriously about who Detroit was coming alive for, who was being pushed out, and what was being lost in that process. Outside the small bubble of revitalization in downtown is where you find the people who are the most passionate about the long, hard, and often painful history of the places and of the city where they live and work. Helping to preserve these sites and the stories they represented during Park Break made me feel like I was doing a small part to preserve Detroit’s (pardon the pun) soul.

Ariel Schnee is a writer, researcher, and Public History Master’s Candidate at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, CO. She can be reached online at www.schneepublichistory.com, or by email at aschnee@colostate.edu.